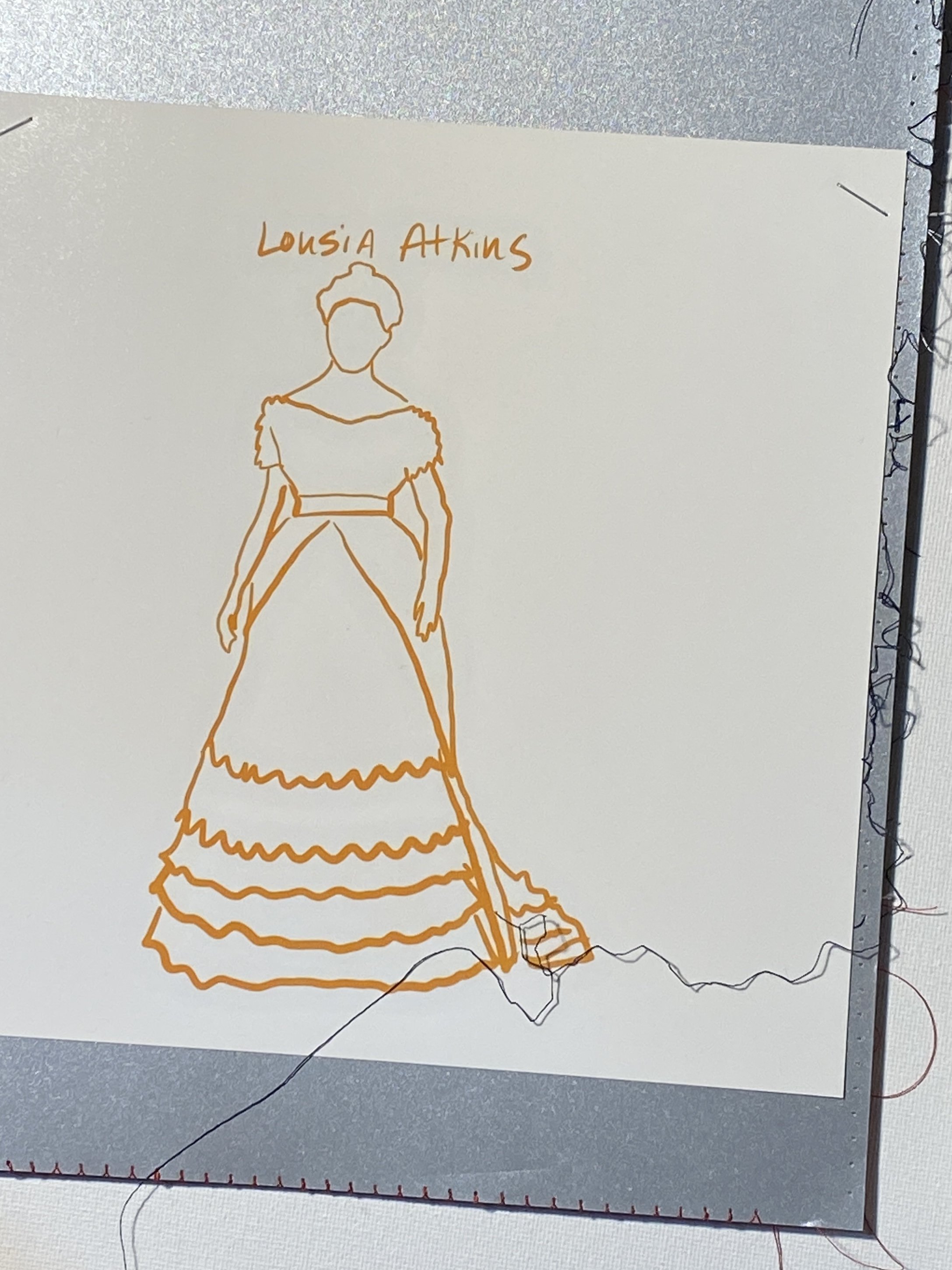

Dr. Louisa Atkins - The Widow

Louisa Catherine Fanny Atkins

#3 of 7 (1867 - 1872)

The Zurich 7

Ueber Gangraena Pulmonum bei Kindern

Dr. Louisa Atkins made it into The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science.

Late 19th century. British physician. Married and widowed. Educated London; University of Zurich (entered 1867; M.D. 1872). Professional experience: private practice, England.

She completed the five year degree “only by dint of extraordinary self-discipline” [TBDOWIS, 58].

From London

Louisa was a young window, her husband died in India. She was a friendly, gentle woman with little science and wrote about how discouraged she was by the difficulties of medical study.

Zurich, Switzerland

1867

Starts school in Zurich alongside Frances

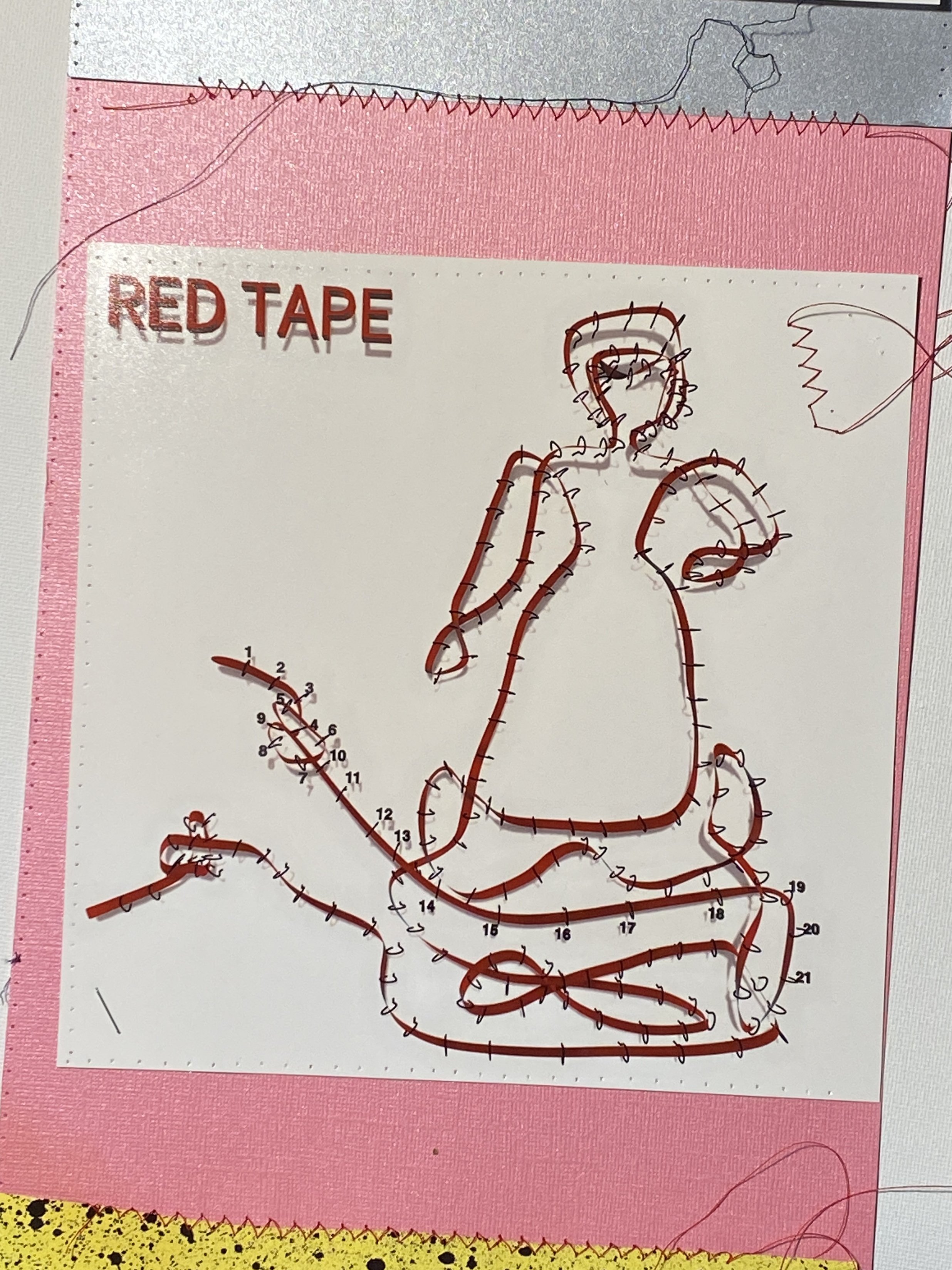

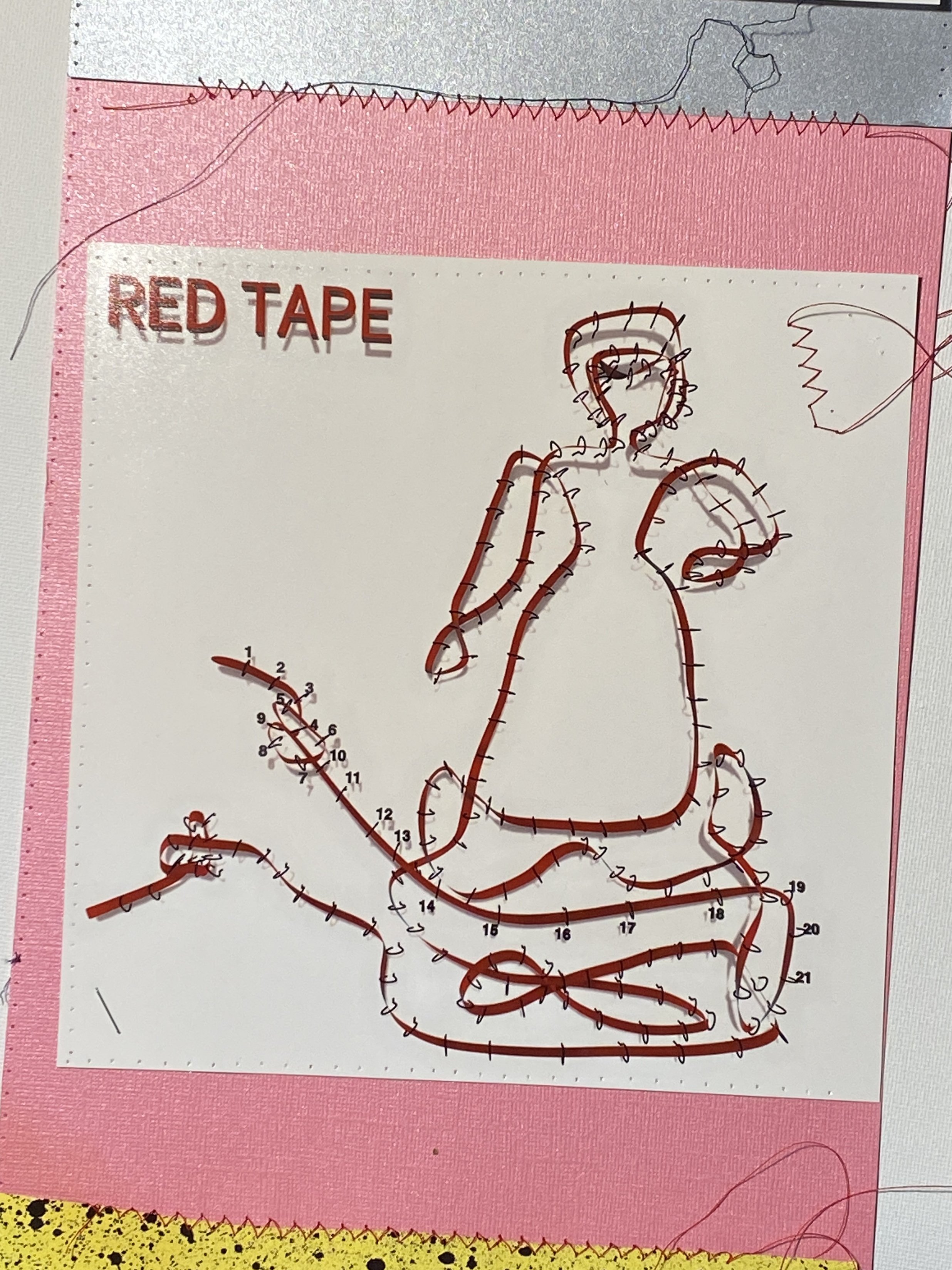

Some women in the UK, frustrated by the lack of available higher education continued “the quiet route” through traveling oversea for training at a foreign university and return to practice unregistered.

1868

Summer Maria Bokova and Eliza Walker arrive in Zurich

1872

Her extraordinary self-discipline enabled her to finish her degree in 5 years with a thesis on pulmonary gangrene in children.

Louisa Atkins M.D. University of Zurich appointed to Birmingham and Midlands Hospital for Woman

Back in England

1872

Louisa was selected as house surgeon for the Birmingham and Midland Hospital for Women over two male registered candidates. The appointment became controversial because Dr. Louisa Atkin’s name did not appear on any official registry because her degree was obtained from a foreign university. She was criticized for taking “the quiet route” by traveling to Europe for a degree and returning home to practice medicine without registration. The was the only available route since “the apothecary route” closed after Elizabeth Garrett Anderson made it through.

When questioned about their choices, the hospital committee stated that they had every reason to be satisfied with their decision. (BMHW Annual Report 1873, HC/WH/1/10/1, BCA)

The Birmingham and Midland Hospital for Women was the first institution to appoint a female house surgeon. Proving that the hospital fully supported women’s path they hired two additional women as house surgeons: Edith Pechey and Annie Reay Barker [BWSATP, 18].

1873

While Louisa made a very positive impression within the hospital, “The quiet route” came under attack from within. Two of the loudest voices in England on the medical education of women were Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Jex-Blake. In 1873, after Jex-Blake lost her legal battle with Edinburgh University Senate. Garrett Anderson recommended women should seek training overseas and practice, until the medical corporations recognized that women in medicine were a fait accompli (Times 5 Aug. 1873). Jex-Blake argued “this put medical education out of reach for almost all women and accepted current injustice” (Times 23 Aug. 1873).

[in 1873 Queen’s College staff and students resisted a strong effort to admit women, it was well published, especially in the Enginslishwoman’s Review July 15 1873]

1874

After significant differences with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Louisa Atkins resigns from Birmingham and Midland Hospital for Women [BWSATP, 36].

1876

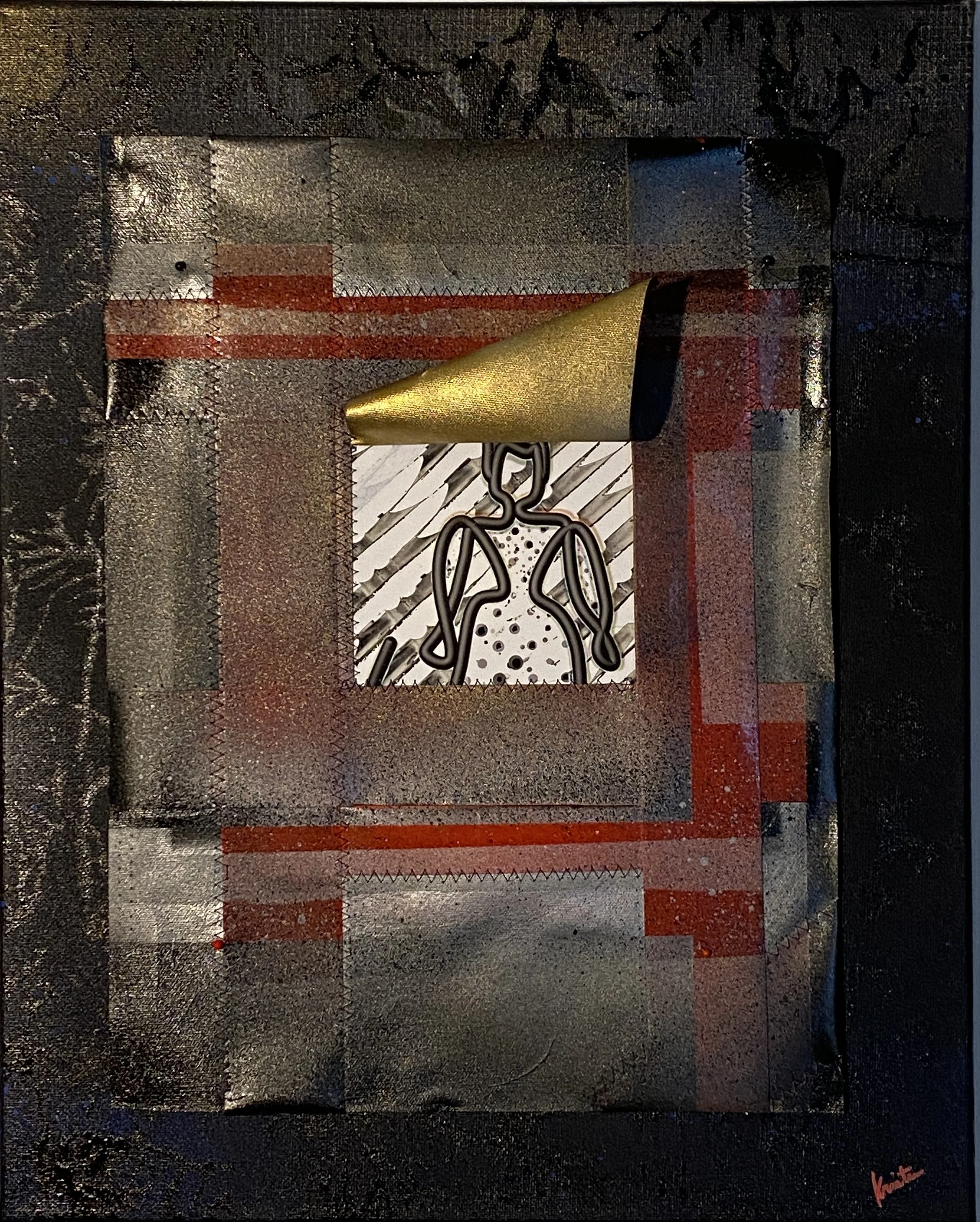

The revised Medical Act was passed, which enabled, rather than required, licensing bodies to recognize ‘any qualification for registration granted by such body to all persons without distinction of sex’ (Anon., The Law Reports (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1876), 289).

“The first medical body to permit women to take its licensing examinations was the Kings and Queens College of Physicians in Ireland (KQCPI)”

1877

Eliza Walker Dunbar (#6 of #7) became the first woman to be licensed by the College in January, Louisa was registered the following year along with Frances. (Dr. Frances Hoggan resignes from the New Hospital for Women very likely because of her opposition of EGA)

1888

Louisa fought professionally with Garrett Anderson and had raised concerns about her surgical competency. When her concerns were not addressed adequately by the management committee of the hospital, she was left with no option but to leave her position the same way Dr. Frances Hoggan left in 1877 and another surgeon in 1888). Louisa left the staff of the New Hospital for Women (NHW) and withdrew as a member of the ARMW (Association of Registered Medical Women - formed in 1879 before women were allowed on the professional registry).

The resignations of two founding members of the ARMW further demonstrates the discord that existed among the first generation of female medical graduates. As Elston notes, such disagreements between the early medical pioneers reveal a tension between the ideals of professional community, and individualistic conceptions of the role of women doctors.

For many, Garrett Anderson’s elevated position within the profession was problematic; as the first woman to qualify in Britain, she was, in effect, irreproachable.

Further Reading:

[BWSATP] Brock C. British women surgeons and their patients, 1860-1918. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.