Sofya Kovalevskaya

Although relatively unknown outside of mathematical circles, Sofia Kovalevskaya is widely regarded as one of the most important women mathematicians prior to the 20th century. However, Kovalevskaya's significance goes far beyond her achievements in math. Her story is an inspiration and now you can step into it. Introducing the Sofya Kovalevskaya virtual museum.

Step into 'The Tangled Life of Sofya Kovalevskaya,' and unravel the intricate threads of a groundbreaking 19th-century mathematician.

Get caught up in the twists, turns, and knots as you explore how Sofya wove her way through societal norms and educational barriers to leave an indelible pattern on history.

As a pioneering mathematician and scientist, Sofya Kovalevskaya made significant contributions to several fields of mathematics including analysis, differential equations, and mechanics. Her work on partial differential equations and the Cauchy-Kovalevskaya theorem remains influential in the field of mathematics today. Her success and groundbreaking achievements challenged the societal norms of her time, as women were not typically allowed to pursue higher education or careers in academia. Her story serves as a reminder of the barriers that women have faced throughout history and the importance of breaking down those barriers to achieve progress and advancement in all fields.

In addition to her contributions to mathematics and science, Kovalevskaya was also an advocate for women's rights and social reform. Her advocacy and activism helped pave the way for future feminist movements and demonstrated the important role that women have played in shaping social and political reforms throughout history. Kovalevskaya's life and legacy continue to inspire and empower women in the fields of mathematics, science, and beyond. Her story is a reminder of the importance of pursuing one's passions and fighting for equality and social justice.

Sofya the Child

-

General Vasily Vasilievich Korvin-Krukovsky was an artillery officer in the Russian Military. In 1843 he inherited two large estates called Palibino and Moshino. Combined the properties represented approximately 9400 acres of land in the province of Vitebsk (now within the boarders of Belarus).

The fourty-four year old General married the beautiful twenty year old Elizaveta Fyodorovna, granddaughter of famed astronomer F.I. Shubert. She never learned to manage a household and was often treated more like a daughter than a wife leaving the management of the to the well established servants. Later that year, Elizaveta gave birth to their first child, a daughter the strikingly beautiful Anyuta, which the family referred to as Anna.

-

Sofya was born January 15 1850, the second child of General Vasily Vasilievich Korvin-Krukovsky a retired military officer. The fifty-one year old General had been at the gambling table the night before, losing so badly at high-stakes cards he was forced to pawn his wife’s jewels to cover the debts. The arrival of a second daughter was a great disappointment for both father and mother.

Her older sister Anna was now 6 and was the star of her mothers eye.

Sofya’s birth did not bring much excitement into the home, both parents had desperately wanted a son.

-

The General was posted in Kaluga, where the family lived until 1858 with a nanny and a governess for the girls. The first born son, Fedor, was born and received waves of attention from mother and father. When entertaining guests, Anna or Fedor were called down from the nursery to present themselves in the drawing room, but rarely was Sofia requested, she was an outcast of the children, loved most by the children’s nurse Praskovia.

Sofya had some peculiarities. She grew more shy and inward, fearful of other children and things that were unusual. The sight of a doll without its head or an unfinished building could cause dark feelings of anguish and distress to overtake her. The comforting arms of her nurse was the only remedy.

-

At the age of 57, the General retired from the army and relocated from the outskirts of Moscow to manage the family's Palibino estate. The move was prompted by rumors of the impending emancipation of the serfs. The General wanted to oversee personally due to his leadership role in the local gentry as Marshall of the Nobility for the Nevel district.

The estate boasted herds of cattle, sheep, and dairy cows, along with flower and vegetable gardens, a vodka distillery, forests filled with game and lakes filled with fish. The bounty of the property were transported for sale to the nearby villages of Vitebsk and Dvinsk.

The manor house was a grand building, built by serfs using local materials, and was the hub of the family's frequent and lavish entertainment. There was a ballroom, home theater, greenhouse and many guest rooms along with housing for all the servants and their family. The General, being the Marshall of Nobility for the region hosted lavish dinners, balls and home-produced plays.

-

Prior to the family's relocation to Palibino, the house underwent renovation. The wallpaper used in the renovation was ordered from St. Petersburg, which was 500 verst away (over 300 miles).

Unfortunately, the family ended up being one roll short. Initially, they planned to order an additional roll from St. Petersburg, but they never got around to it and assumed that no one would ever see the unfinished nursery.

To complete the walls, the family decided to use the old papers found in the attic. As fate would have it, someone stumbled upon a stack of lecture notes that belonged to the father's course on differential and integral calculus taught by Mikhail Vasilyevich Ostrogradsky (1801–1862) a prominent Ukrainian mathematician known for his significant contributions to calculus of variations, number theory, algebra, and mathematical physics, including the Ostrogradsky-Gauss theorem, or the divergence theorem.

Though she couldn't comprehend the hieroglyphics' meanings, she recognized their significance and found them fascinating. She would stand for hours poring over the papers, reading and re-reading them until she had memorized lines of formulas by heart, even before she understood what she was reading. One formula, prominently displayed at the wall's center, concerned infinitesimal quantities and limits. Later in life, this knowledge would prove beneficial when she studied under Professor A. N. Strannolyubsky in Petresburg, who was impressed by her comprehension, exclaiming, “You have understood them as though you knew them in advance.”

-

Sofia and her siblings were raised by nannies and governesses who taught the children the basics of languages and music.

Around 11, Sofya’s Uncle Peter introduced her to mathematical concepts which would have a strong influence on the young girl. They had conversations on infinity and asymptotes - straight lines which a curve steadily approaches, but never reaches. These concepts seemed somehow secretive and particularly attractive to her unique mind. The general did not care for the influence Uncle Peter had on his young daughters and insisted he stop influencing them saying “Such silly pretenses and frantic exertion of an immature brain could lead to the yellow house.” At the time, mental hospitals were painted yellow, and the term "yellow house" became a euphemistic or symbolic reference to such institutions. Her father was fearful that engaging in intense mental efforts could lead to a mental breakdown or worse, madness.

The licensed in-house tutor Y.I. Malevich instructed the children in history, geography and basic arithmetic. By thirteen, Sofya started to show a strong aptitude for algebra which appalled her father. He decided to put a stop to any further mathematics study and instructed the governess to make sure his wishes were carried out. Fortunately, Sofya had hidden away one of Malevich’s books, a copy of Louise Bourdon’s Algebra which she read in secret at night. Malevich would wait until Sofya turned 15 to formally tutor her in algebra with the introduction of first degree equations, also known as linear equations.

At 14, their neighbor N.N. Tyrtov, a professor of natural philosophy (physics) came for a visit brining along a copy of his new textbook. Sofya promptly claimed it, eager to explore its contents. Her curiosity was soon met with frustration, as she encountered complex trigonometric formulas and unfamiliar terms. Malevich, the family's tutor, was systematic in his teaching approach and unprepared to assist her with these concepts, avoiding her questions, but Sofya was undeterred. Using her understanding of chords as a substitute for the sine function, she managed to make sense of the material, since it dealt exclusively with small angles. Her inventive methodology succeeded!

At first, Professor Tyrtov was reluctant to believe that at 14, Sofya had worked her way though such complex ideas in a original way. After a lengthy discussion the professor when to the general insisting that Sofya be given serious training in mathematics comparing her with a modern day Pascal.

“I often heard my nurse say that Aniuta and Fedya were mama’s favorites, and that mama disliked me. I do not know whether this was true or not, but nurse always said it quite regardless of my presence.”

Polish Influence

“Most of the surrounding landowners were old Poles, the young ones had either perished in the rebellion of 1862-1863, or had been exiled to Serbia.”

-

The family of General Lorvin-Krukovsky took great pride in their diverse heritage. The story goes that their lineage can be traced back to King Matthias Hunyadi of Hungary, also known by the nickname Korvin. He was a courageous warrior, a supporter of arts and literature, as well as a lover of books. One of the king's daughters fell head over heels for a Polish knight named Krukovsky. The couple tied the knot, made their home in Lithuania, and thus founded the Korvin-Krukovsky family line.

-

“I inherited my passion for science from my ancestor the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus; my love for mathematics, music and poetry from my mother’s grandfather, the astronomer Schubert; my love for freedom from Poland; my love for wandering and my inability to obey the accepted tradition from my Gipsy great-grandmother; and all the rest comes from Russia.”

(Sofya describing her ancestors to her Stockholm friends and writer Ellen Key.)

-

“Most of the surrounding landowners were old Poles, the young ones had either perished in the rebellion of 1862-1863, or had been exiled to Serbia.”

Sofya passionately aligned herself with the Polish cause and even began secret Polish language sessions with Malevich. She found herself captivated by the young and charming Polish landowner Buinitsky, who took an interest in her, especially given her support for the rebels.

-

The Serf Emancipation of 1861 in Russia was a significant event in the history of women's rights, as it marked the first time that women were included in a major social reform movement. Women played a key role in the movement for serf emancipation, advocating for greater rights and freedoms for themselves and their families.

Peter the Great established a Table of Ranks. The table consisted of fourteen military and civil ranks, the top eight of each were limited to nobility. Marshal, lieutenant-general, general where the highest ranks, they wore gold stars reflecting their position and were addressed as “Your Excellency.” The nobility were a higher favored class that controlled the military, civil government and was perpetuated through marriage. Boys could work their way up the ranks on the civil side by started as pages, or entering the cadet corp on the military side, but for girls there was no position, path or opportunity for advancing except through a husband or male relation.

On the other end of the spectrum were the serfs, tied to the land, unable to travel. A few serfs also owned other serfs, acquired land or even factories all under the ownership of the noble landowner. Sefs who worked the land owed the landowner annual rental in cash, produce or service, they were not free.

Sofya was 11 when the decree from Tsar Alexander II emancipating serfdom was announced in the village church, the priest read the manifesto to a crowed and confused congregation. The manifesto is littered with convoluted, judicial language. Everyone strained to interpret the meaning, especially the serfs, most of whom lacked any formal education. When the priest finished, most were still confused with the result.

The Emancipation Act only granted freedom to the serfs, in two more years another law would be passed specifying that male agricultural serfs could buy their land without owners consent if they had the payment. Loans could be obtained by serfs with the consent of the landowner allowing an allotment of 88 acres, but those loans would eventually tie the peasants down into a deeper bureaucratic hole difficult to escape. (20 years after emancipation, 80% of noble landowners had sold most of their land to the peasants or speculators. This explains some of the financial difficulties Sofya would face later in life).

The General’s two estates likely owned around 300 serfs , 25-30 worked in the household. After the emancipation, the number of serfs remained about the same but they were required compensation, either in cash or extra land. Overtime, the General was forced to cover old debts by selling parts of the estate. Many of the best serfs left the estate when given their freedom, replaced by inferior ones who were less submissive.

-

The January Uprising of 1863 was a significant revolt in the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, under Russian control since the final partition in 1795. Sparked by cultural repression, conscription, and the desire for independence, the uprising began in Warsaw on January 22, 1863, and quickly spread across the region.

Led by the National Government, the revolt sought to restore Polish independence and introduced sweeping reforms, including the abolition of serfdom. Participants included the Polish nobility, intelligentsia, peasants, and other ethnic groups such as Lithuanians and Belarusians.

The Russian Empire responded with a harsh military crackdown, resulting in a prolonged conflict that lasted until late 1864. Despite the insurgents' fervor and determination, the rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful due to lack of international support, internal divisions, and insufficient resources.

In the aftermath, the Russian authorities implemented severe reprisals, executing or exiling thousands, further curtailing Polish autonomy, and pushing forward Russification policies. The legacy of the uprising remains a symbol of Polish resistance and national identity, and its impact continues to be felt in Polish historical memory and culture.

“Initially, Sofya wanted to study medicine to be of use to the political exiles in Siberia.”

Sofya's Older Sister - Anna

-

One day, a registered letter arrived at the house addressed to the housekeeper. The General, Anna’s Father insisted that she open it, only to discover it contained payment for Anna’s short stories published in Dostoevsky's The Epoch. Unfortunately, this happened during a large party, causing the General to lock himself in his study, consumed with fury.

His response to the letter from FD was scathing: "Now you are selling your stories, but the time will come-mark my words-when you'll sell yourself." At first, Anna’s mother pleaded with her to give up writing, citing her own experience with wanting to play the violin as a child, only to be told it was ungraceful for women to handle a bow. Instead, she took up singing, which worked out well for her, and her mother urged Anna to do the same.

However, with time, her mother began to feel sorry for how severely Anna had been scolded and eventually became proud of her daughter's literary accomplishments. After a few days, Anna read her story to the household, with her father sitting front and center. It wasn't until the final lines, as the elderly woman lay on her deathbed, recalling her wasted youth, that both Anna and her father were moved to tears. She had won.

So much so that her father conceded she could continue writing with FD, as long as he was allowed to read their letters. He even expressed a desire to meet Dostoevsky himself the next time they were in Petersburg.

In the same year that FD's brother Mikhail passed away, she published two stories in The Epoch. Meanwhile, her sister Sofya, who was only 14 years old, worked hard to learn Mikhail's favorite piano work, hoping to catch his attention. However, he was too preoccupied with professing his love to her older sister, who was 20 years old at the time.

-

Anna found herself resonating deeply with the character of Vera Pavlovna in Nikolai Chernyshevsky's "What Is to Be Done?"—a narrative that drew inspiration from the real-life story of Maria Obruchova, one of Europe's first female medical doctors. Just like Vera and Maria, Anna felt confined by societal expectations that sought to limit her choices, largely to a traditional marriage designed to elevate her family's status.

Maria Obruchova broke those societal chains by forging a new model of marriage, one premised on equality and individual autonomy. With the assistance of P.I. Bokov, her brother's tutor, she created a partnership that not only allowed her to escape her family's traditional expectations but also to enroll at the University of St. Petersburg, a significant step towards her future career in medicine.

Similarly, Anna yearned for her own emancipation. Fueled by the pioneering examples of Vera and Maria, she sought a life partner who would not just free her from her father's constraints, but also empower her to live life on her own terms, just as Maria had done.

In the spring of 1868, it was Maria who introduced Anna and her close friend Zhanna Evreinova to Vladimir Kovalevsky. A fellow student in St. Petersburg, Vladimir was supportive of young women like them who sought marriages as a way to break free from restrictive home lives.

-

Nizhiny Novgorod Provincial Governor:

“All women who wear round hats, blue glasses, hoods that conceal their short hair and do not wear crinolines, arrest them, make them take off all these garments, and if they resist, exile them from the province.”

Stuck in the countryside, Anna's horizons were expanded by Aleksei Filippovich, the son of the village priest. Unlike his father, Aleksei chose to study natural sciences at a university in Petersburg. When he returned home, he shared bold ideas about human evolution and the absence of a soul, focusing instead on reflexes. Aleksei also secretly brought Anna some banned reading material, like Sovremennik and Russkoe Slovo, as well as a prohibited copy of Herzen's The Bell. Frustrated that her father wouldn't allow her to move to St. Petersburg, Anna decided to become a writer, using a male pen name to avoid attracting attention.

“Now you are selling your stories, but the time will come-mark my words-when you’ll sell yourself.”

St. Petersburg

In February of 1865, Sofya along with her mother and sister traveled to St. Petersburg for the winter. It was here that her old neighbor, Professor Tyrtov, put her in touch with the prominent mathematician at the Naval School A.N. Strannolyubsky.

“Only after some hesitation, my father agreed to invite A. N. Strannolyubsky as a teacher. He and I embarked on the work, and in the course of the winter (‘65-’66) we went through analytic geometry and differential and integral calculus. Strannolyubusky was surprised at how quickly I grasped and mastered the concepts of the limit and derivative as if I knew them beforehand. I suddenly, vividly remembered that all this stood on the sheets of Ostrogradsky [from the walls of her nursery], and the very notion of the limit seemed long since familiar to me ”

“Her work, although not of direct scientific importance, reveals a talent that is completely out of the ordinary, especially when you consider that it came from a 14-year old girl!”

The sisters returned to St. Petersburg over the following winter (‘66-’67).

While Sofya was busy with mathematics, Anna continued her work as an authoress, visiting frequently with her friend Dostoevsky and striking up personal acquaintances with like minded young women all advocates of higher education for women including Nazezda Suslova and Maria Obruchova who along with The Zurich Seven would become the first professional women medical doctors.

By the spring of 1868, Maria Obruchova, then married to Dr. P.I. Bokov introduced Anna to her future best friend Zhanna Evreinova (Anna Mikhailovina Evreinova who would later go on to become the first woman lawyer in Russia) along with Vladimir Kovalevsky a student in St. Petersburg. Anna and Zhanna hatched a plan with Vladimir where he would marry one of the girls allowing them both to travel to Europe properly chaperoned by a married couple.

Switzerland and Germany

During the summer of 1866, the family traveled to Switzerland, bringing along the family tutor. In his letters and memoir Malevich recalls he had just started to go through second degree equations with Sofia where she gained a very solid understanding of algebra. By the time their travels took the family through Montreux and the baths of Germany Sofya had mastered second degree equations as well as portions of higher mathematical studies. The intend was to move onto trigonometry once the family was settled back in Russia.

Vladimir

-

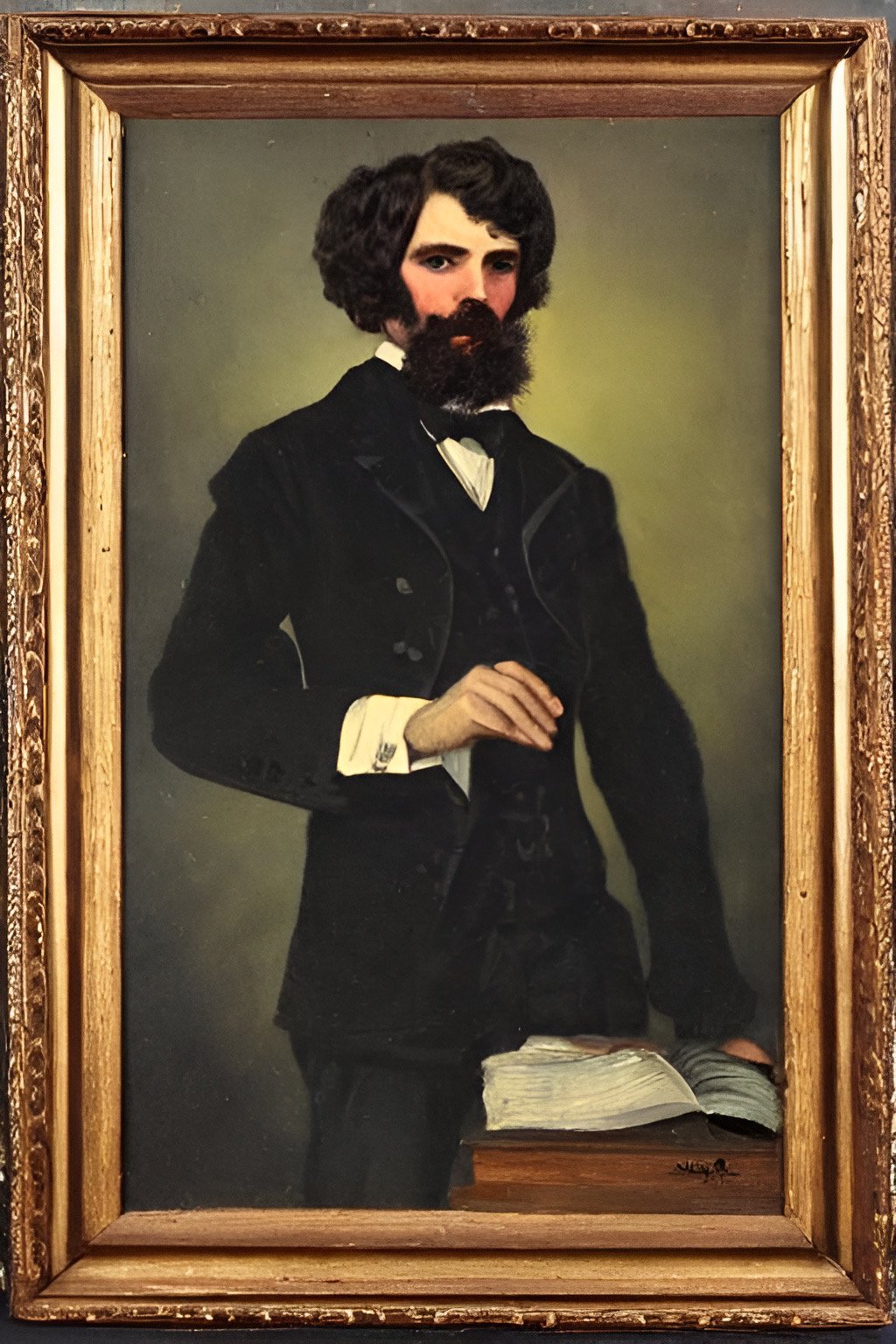

Vladimir was a Russian paleontologist who graduated from the School of Jurisprudence in 1861. Upon graduation, he started working with the department of heraldry, but asked for permission to travel abroad for his health.

He went to Heidelberg, Tubingen, Paris, Niece and finally London where he gave lessons to the daughter of Alexander Herzen, a prominent Russian intellectual and writer of the 19th century, known as the "Father of Russian Socialism," who advocated for political reform, human rights, and social change through his writings, activism, and founding of the Free Russian Press while in exile in Western Europe.

Throughout 1971 Vladimir studied fossils of vertebrates across Germany, France, Holland and Great Britain attending lectures and museums at each stop, he added to his fossil collections while in France and Italy.

With his brother, Alexander Onufrievich Kovalevsky, a distinguished biologist and a pioneer in comparative embryology he translated, edited and published, works by Charles Darwin, Charles Lyell, Louis Agassiz, and others. In 1972 he translated Darwin’s “Expressions of the Emotions of Man in Animals.”

With the encouragement of Sofya, he submitted his doctoral thesis on the paleontology of horses at the University of Jena in 1872.

Between 1873 and 1877, Vladimir wrote six papers on large, hoofed, herbivorous mammals, specifically the perissodactyls (odd-toed) and artiodactyls (even-toed), in three different languages (none of which were Russian). His papers were published in various journals, including the German journal Palaeontographica and the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. His most famous French treatise was published by Memoires de l’Academie Imperiale des Sciences de St. Petersbourg and focused on the evolution of horses.

Vlad's work received praise for introducing evolutionary ideas into paleontology to help better arrange large groups of otherwise undifferentiated mammals. He looked at correlating changes in anatomy with a changing environment and identified a correlation between changes in hooves and teeth and a shift from browsing leaves in woodlands and marshes to grazing grasses and running in the open. Thomas Henry Huxley had come to the same conclusion, but lacked the extensive documentation of Kovalevsky.

By 1976 Vladimir was informed by Huxley that he was mistaken about the evolution of horses, as the transitions occurred in America, and Europe only recorded a few end members before the American horses were wiped out.

The news was devastating Vladimir, his life’s work had been proven wrong.

Upon returning to Russia he secured the position of Associate Professor at Moscow University from 1880–1883.

His exploits include a stint as a failed oil tycoon which eventually lead to the financial ruin of the couple, the disintegration of their marriage and the end of his life by his own hand.

The Marriage Proposal

“My first business in Petersburg, of course will be to make an inspection and selection of the most suitable materials for the preparation of preserves, as per your commission. We shall see how this new product will succeed”

The letter contained a coded message intended to mislead the girls’ father if he chose to exercise his paternal prerogative to read his daughters' correspondence. The term 'preserves' was the chosen code word for husbands, specifically fictitious husbands. This concept was a desperate necessity for young women who wished to free themselves from parental oversight so they could leave Russia and pursue professional training.

Given that Russian law rendered obtaining a divorce nearly unattainable, opting for a fictitious marriage as a means to gain independence was fraught with risk for both men and women. This strategy, pursued by Anna and many young women of her generation, may have been influenced by the relationship portrayed in Nikolay Chernyshevsky's novel 'What Is to Be Done?' It's worth noting that such a course of action was not only daring but reflected the larger societal constraints and aspirations of the time, particularly for women seeking autonomy and self-determination.

Originally, the plan was to find a suitable husband for Anna, but when Sofia tagged along to one of their meetings, Vladimir insisted he would go along with the plan only if he could marry Sofya. In a long letter to Sofya he promises his dedication to her along with the women in her life also fighting for their own personal goals. He is certain Sofya will become a scholar in the natural sciences, that her sister Anna will be a gifted writer, that their mutual friends Nadezda and Maria will become excellent physicians and that the distinguished professor Ivan M. Sechenov will always remain their dearest and mutual friend.

Knowing their father the General would not approve of the marriage, Sofia decided to take bold action. She chose the evening of a dinner party at the house to make her move, deliberately failing to appear at the table and leaving a message that she was busy preparing her wedding plans with Vladimir. Her father, the general, had no choice but to pretend to know about the engagement in front of his guests to avoid a scene, effectively blessing the union publicly and making it difficult to retract. At last, Sofia was free to pursue her education without impediments. The couple eventually married in September of the same year and received a blessing at a Russian Orthodox church. Just three days after the wedding, the Kovalevskys arrived in Petersburg, ready to start their new life together.

“Meeting you makes me believe in the affinity of souls, so swiftly and genuinely did the two of us come together and become friends I cannot keep from picturing much that is joyous and good in our common future.

Therefore you should look on me now, not as a man doing you a favor, but as a comrade striving jointly with you toward a single goal; that is, I am exactly as necessary to you as you are to me; therefore, make use of me accordingly, and entrust to me whatever you may take into your head without fear of burdening me; I shall work just as much for you as myself”

“The wedding bells had only just died down and the euphoria of her new freedom subsided, however, when Sofya became aware that her problems had only just begun — were, indeed, so vast in dimension that their outlines could not even be delineated”

The Kovalevsky’s in St. Petersburg

In 1864 the Tsar officially banned all women from universities within Russia, no exceptions were made, but Sofya managed to take help from sympathetic professors and friends. Sofya felt guilting being a “free” women in St. Petersburg while her older sister was still shut away in the countryside at the Palibino country house.

“Sechenov’s lectures begin tomorrow; and so my real life begins at 9 a.m. ...Vladimir and friends will escort me by way of the back stairs so that there is hope of hiding from the administration and from curious stares.

I forgot to tell you that Mechnikov promised to admit me to his lectures and get permission for me to attend the physics lectures, I’m studying physiology and particulary anatomy; we got a skeleton from Pyotr Ivanovich Bokov and brother (Vladimir) is poking it at this moment.

Sometimes it’s horribly painful for me to be without you. You are necessary to me, more necessary, believe me, than you ever were in my life.

Alexander Onufrievich (Vladimir’s older brother) is a strong Nihilist and he advised me, in case they exclude me from Ivan Mikhailovich Sechenov’s lectures, to dress myself in male clothing.”

Maybe it becomes too difficult for Sofya to continue classes in St. Petersburg. It is unclear the exact reasons why, but the young couple makes plans to cross the German boarder in April of 1869. No suitable marriage candidates could be found for Anna and her close friend Zhanna. Professor Mechaikov had selected a bride for himself and Professor Sechenov was essentially “married” to Maria Bokova leaving no option than for Anna to travel as a spinster with the married couple.

Zhanna, who’s father proclaimed he would rather see his daughter in the grave than in a university remained longer in Russia until mid-November when she ran away from home and illegibly crossed the boarder on foot under fire from the Russian boarder patrol.

Vladimir’s Letters To Charles Darwin

As a paleontologist and publisher, Vladimir had frequent correspondences with Charles Darwin, being the first person to translate and publish his works from English to Russian. Darwin’s work was incredibly popular in Russia at this time. Their letters, spread out over more than a decade provide a rare and unusual glimpse of the life of Sofya and Vladimir. Excerpts of their corrispondences have been taken from the University of Cambridge’s Darwin Correspondence Project.

“During this long time of silence I have changed my former state, and am now a married man; my young wife is a woman of quite an exceptional turn and, not being what you call strong minded at all, has a passion for natural science, especially mathematics & natural philosophy (physics) this induced me also to leave for a time my editing and to become student myself; we go together in April in some small German university and will live there for two or three years to prepare ourselves for a long scientific travel in Siberia or in Central Asia. I hope you will help me in this with your large experience and knowledge.

I hope Mrs. Darwin and your daughters are all well, and if they have not forgotten me I beg to give them my hearty compliments.

I, that is we, hope to see you this Summer, as we shall be in Germany and will make in the Zwischensemester an excursion to London.”

-

From V.O. Kovalevsky 13 September 1869 to Darwin

I left Russia in March and passed the whole summer in Germany at Heidelberg devoting myself entirely to Geology and have now a reasonable hope to regain the time lost by me these five years, while affairs dragged me away from regular studies. My wife was happy enough to be accepted in the University as a regular student and worked so well that in eighteen months or two years she will be able to pass her examination as “Doctor der Mathematik und Physik".

In the vacation I travelled about five weeks in Switzerland, am now in Paris and hope to be in London, though my chief attraction in England will be Down. If you have not quite forgotten Your visitor of 1866 & editor of Your book be so kind as to write me two lines to Paris (W. Kowalevsky, Paris. Boulevard Montparnasse, Rue Vavin, Hotel Heranger N 4.) to inform me wether You will be able to receive our visit.

I am very Impatient to see You once more and my wife is the more so to make your acquaintance.

-

From V.O. Kovalevsky 20 February 1870 to Darwin

“How is progressing the work on Man, I hope to receive some sheets in April by Your Kindness, my wife send her salute to Mrs. Darwin and the ladies,—we were separated the whole winter, she working at her mathematics at Heidelberg, and I sticking in the Museum of Munich, in three weeks the vacation begins and we go to Nizza, in the autumn We hope once more to see You in England.”

-

From V.O. Kovalevsky 28 February 1870 to Darwin

My wife wished to go to Berlin, and the Rector the know physiologist Dubois Reymond was one of our advocates, and a better one is difficult to have, but the mathematicians were against it, holding to the strict sense of the law. Generally the mathematicians are the worst thing living, not only in Germany but also in our country and I hope in England. One of the principal opponents to the admission of ladies was Kunt, a true pure, who at one of the Natural Science Congress proposed a toast “for the theory of numbers (Zahlenteorie) as a part of mathematics that till the present was not besmeared with practical application”. So are they all, more or less. But happily Kirchhow took a great interest in her and promised to give her a special investigation about light in the summer, so she remains a suer at Heidelberg. For my part I am quite uncertain what to do, going to Vienna and working with the assistance of Tehermak and Suess, or going to England and working alone without direction. I think I’ll take the latter course; firstly because with Your kindness to me I will have as good assistance as can be; secondly because I will have the use of the best collections existing.—

-

From V.O. Kovalevsky 15 August 1870 to Darwin

Dear Sir

I am once more for a short time in England and should be very happy to see You if You could accept my visit. It is such a long time I had no news from You; after Your letter to Nice in the Spring I wrote You from a small place near Marseille, but having no answer I fear my letter has been lost. My wife is gone with her sister to the sea side and I am left alone to make excursions; if You are not occupied to much to receive visits, I have an intention to go to Bickley Tuesday and walk from the Station to Down.

I hope to find Mrs. Dawin and the ladies in good heal.

Yours | truly | W. Kovalevsky

-

From Sofia Vasilyevna Kovalevskaya and V. O. Kovalevsky

London.

1 September. 1870.

Sir!

I am exceedingly thankful for your kind offer to procure me some books from the library of the Royal Society and though I really fear that I am misusing your kindness, but the book is so indispensable to me, that I decide myself to profit by it. We ascertained today, that the Royal Society is opened the whole month of September, and the book for which I should ask you an order is Jacobi. Fundamenta nova theoriae Functionum ellipticarum. It is not a rare one and could be easily replaced in the improbable case of some misfortune happening to it.

I hope, that you will allow me in the course of the autumn to express you personally my thanks for your kindness. Remember me kindly to Mrs. Darwin and the Ladies. I am glad to hear, that your excursion to the country has done your health a great deal of good.

Believe me Sir | Your’s truly | Sophie Kowalewsky

P.S. May I ask You Dear Sir if You know something of the dredging expedition of Mr Carpenter, I know he is at Gibraltar with the Porcupine, but will he enter the Meditteranean or confine himself only to the Atlantic, I received to day a letter from my brother asking me where Mr. Carpenter is; he would not shun a trip from Naples even to Tunis or Algeria if he has a chance o meeting him there.—

Yours truly | W Kovalevsky

-

Dear Sir,

I did not write You such a long Time not being quite sure shall I remain at Berlin or go to Leipsic, and although my wife was not admitted to the University here we resolved to remain at Berlin there being here so many means of pursuing studies privately.

-

Vladimir to Darwin 2 June 1971

My wife is working very hard and hopes to pass her examination this winter, the Parisian events robbed us of a precious time and peace of mind indispensable for serious study.

-

Vladimir to Darwin 20 January 1974

20 Jan 1974

My wife is also very well and presents her compliments, she is hardly working at something very intricate about the stability of Saturn rings, but the matter seems to be so difficult that we don’t clearly see when there will be an ⟨end⟩ of it. Clark Maxwell wrote an elaborate memoir on the same subject in 1859, but we could not, even at the Observatory of Berlin get it here, and I am going to ask Murray to hunt me up a copy in England.

24 Jan 1974

My dear Sir

I have ordered my bookseller to send Clerk Maxwells’ book to you published by Macmillan & Co & I suppose it will reach you in a few days.— Please present it from me to M. Kowalevsky.

Maxwell says M. Hirn has lately published on same subject; “but the dynamics are at best, moderate”—

Yours sincerely | Ch. Darwin

27 Jan 1974

Dear Sir!

I have been absent for a couple of days and found Your very kind letter only yesterday upon coming back. You are really too kind and I am ashamed of having given You this trouble with Maxwell’ Saturn. The memoir is in reality so seldom met, that even the President of the Paris Academy Mr Faye, presenting an asbtract upon another paper on Saturn said that he could not see the memoir of Cl. Maxwell anywhere, but only a short notice on it by the Astr. Royal Pr. Airy. But indeed this was too much of having made Your Son, whom I present my best thanks, write to Profess. Maxwell.

With my best thanks | Your very truly | W. Kowalevsky

P.S. My wife presents her best thanks to You and is really ashamed that my former letter led You into such trouble, she is very much obliged to Mr G. Darwin for having written to Cl. Maxwell.—

-

To G. H. Darwin 9 December 1880 from Charles Darwin

My dear George

The Kowalevskys have been to lunch & a very interesting visit it was. Madame has been greatly interested by your papers & if you can spare a copy of your last one do send her one to “13 Montagu Place Russell Sqr.” I never saw such a funny little woman she bubbled over with enthusiasm about Sir W. Thomson’s papers & work. She was indignant with Cayley & declares that he makes his work far more difficult than it really is.

Yours affect | C. Darwin

Sofia and her husband, had initially planned to visit Down on November 25, but the visit did not take place (refer to the letter to V. O. Kovalevsky, dated November 25 [1880]). Between December 7 and 11, 1880, the Darwin family was in London, as indicated by entries in Emma Darwin’s diary (Source: DAR 242).

George Darwin had been tackling mathematical problems linked to the rotation of viscous or elastic bodies. His latest research paper, titled ‘On the analytical expressions which give the history of a fluid planet of small viscosity, attended by a single satellite’ (Published: G. H. Darwin 1880), explores this subject. Meanwhile, Kovalevskaya had a keen interest in studying the rotation of a rigid body about a fixed point, a topic on which she later produced a prize-winning essay (Published: Kovalevskaya 1889). To learn more about her mathematical contributions, refer to Koblitz's work from 1983.

Arthur Cayley held a professorship in mathematics at Cambridge University. Known for his work in thermodynamics and determining the age of the earth, William Thomson had been a source of encouragement for George in his work on secular cooling.

Heidelberg

“Sofya single-handedly persuaded Heidelberg University to break its prohibition against women, opening the door for herself, Julia Lermontova and Natalia Armfeldt. These women received instruction from the top professors in Europe including Gustav Kirchhoff, Robert Bunsen, Hermann Helmholtz, Leo Konigsberger and Paul and Emil Du Bois-Reymond. ”

Sofya and Vladimir depart St. Petersburg in April of 1869 and travel to Heidelburg, her to study mathematics, him to study geology and paleontology. Sofya was shocked to discover that the university did not allow women to study as regular students. She was persistent in her insistence to be allowed to study, eventually getting permission from the university to attend lectures on an unofficial basis.

-

In the spring semester of 1869, Sofia registered as an auditor and took on a heavy course load of 22 hours, with 16 hours dedicated to mathematics. However, her life was not the ideal she had pictured, and the arrival of Julia Lermontova and the trio lived and worked together under fairly ideal circumstances.

During this time, Sofia penned a poem called "The Husband's Complaint," in which the husband expresses his shock at discovering that his wife was serious about continuing her studies. He had carelessly assured her that she could do so, and now she was making his life miserable by holding him to his promise. Although he might have had many phobias and required her companionship, he was annoyed by how content she was to sit back and read while he did nothing.

-

In the fall, Sofya, Vlad and Julia were joined by Sofya’s sister Anna Korvin-Krukovskaia and hopeful law student Zhanna Evreinova

Evreinova had escaped from Russia with the help of Vladimir and sent a letter of thanks to his brother, which resulted in his arrest. Vladimir had to borrow 3,000 rubles from Sofia's father to secure his release.

The two newcomers brought hostility and antagonism to Vladimir making their opinions clear that they considered any intimacy between Sonia and Vlad inappropriate and made sure that everyone was aware of it.

Eventually Vladimir would move into his own living quarters and eventually leave to continue his studies throughout Europe.

Zhanna was unsuccessful in gaining admittance to the university as a law student so she moved on to Leipzig while Anna returned to Paris to join the growing revolutionary activities.

-

During the spring, Paris was surrounded by the Prussian army, and the French National Guard, which had defended the city, was fighting with the National Assembly (which was negotiating with the Prussians). Anna had fallen in love with Victor Jaclard, a fiery revolutionary introuble with the French goverment. The couple fled to Geneva to escape his imprisonment.

With the news of Napoleon’s capture the couple returned to Paris in September just as the new Republic was proclaimed.

By January of the following year, 1871, Paris was surrounded by German troops and the city was left to starve and defend itself for the next 10 weeks.

Despite the danger, Vlad and Sofia snuck into Paris in an old rowboat, carrying a first copy of Darwin’s “Decent of Man” across Prussian lines.

They lived and worked in the commune from April to May, leaving when it seemed like the situation was not sustainable.

Not long after they traveled to Berlin, the commune fell to Theirs forces, and Anna and her fiancé Jaclard found themselves in trouble. Anna’s father, the general, came to Paris and used his relationship with Theirs to ask him to turn a blind eye to Jaclard's escape.

“Sofya immediately attracted the attention of her teachers with her uncommon mathematical ability. Professor Konigsberger, the eminent chemist Kirchhoff and all the other professors were ecstatic over their gifted student and spoke about her as an extraordinary phenomenon. ”

In the spring of 1870, while Anna had fled to Geneva, Sofia arrived at the pivotal realization that Mathematics was her true passion. Among all the mathematicians in the world, there was one she esteemed above the rest and whom she ardently wished to study under. With recommendations from her professors at Heidelberg, in August of 1870 Sofya traveled to Berlin to meet with the famed mathematician Karl Weierstrass.

If Sofya thought it was difficult to gain access to the University at Heidelberg, it was beyond impossible to officially study in Berlin. The regulations of the university barred women from entering the doors, even on an unofficial basis. Weierstrass was so impressed with Sofya he agreed to teach her privately.

“My wife wished to go to Berlin, and the Rector the know physiologist Dubois Reymond was one of our advocates, and a better one is difficult to have, but the mathematicians were against it, holding to the strict sense of the law. ”

Overview: Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War was a significant conflict between the Second French Empire of Napoleon III and the North German Confederation, led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Here's a general overview with dates and locations:

Prelude (July 1870): Tensions rose between France and Prussia over the succession to the Spanish throne, leading to the Ems Dispatch. France declared war on Prussia on July 19, 1870.

Invasion of France (August 1870): The German states united under Prussian leadership, invading northeastern France. Key battles include:

Battle of Wissembourg (August 4): Wissembourg, France

Battle of Spicheren (August 6): Near Saarbrücken, Germany

Battle of Wörth (August 6): Near Frœschwiller, France

Battle of Mars-la-Tour (August 16): Near Vionville, France

Battle of Gravelotte (August 18): Near Metz, France

Siege of Metz (August-October 1870): Metz, France, where the French were defeated and forced to surrender.

Battle of Sedan (September 1-2, 1870): Sedan, France, where Napoleon III was captured and the Second French Empire fell.

Siege of Paris (September 1870 - January 1871): Paris was besieged by German forces.

Proclamation of the German Empire (January 18, 1871): In the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor.

Armistice (January 28, 1871): The French interim government signed an armistice, ending the active conflict but leaving the Germans occupying parts of France until the final treaty.

Treaty of Frankfurt (May 10, 1871): Formal peace was reached with the Treaty of Frankfurt. France ceded Alsace and much of Lorraine to Germany and paid a large indemnity.

The Franco-Prussian War had lasting impacts on both France and Germany, setting the stage for the alliances and tensions that would ultimately lead to World War I. It marked the unification of Germany and the end of French dominance in continental Europe.