The First Women Doctor in Europe

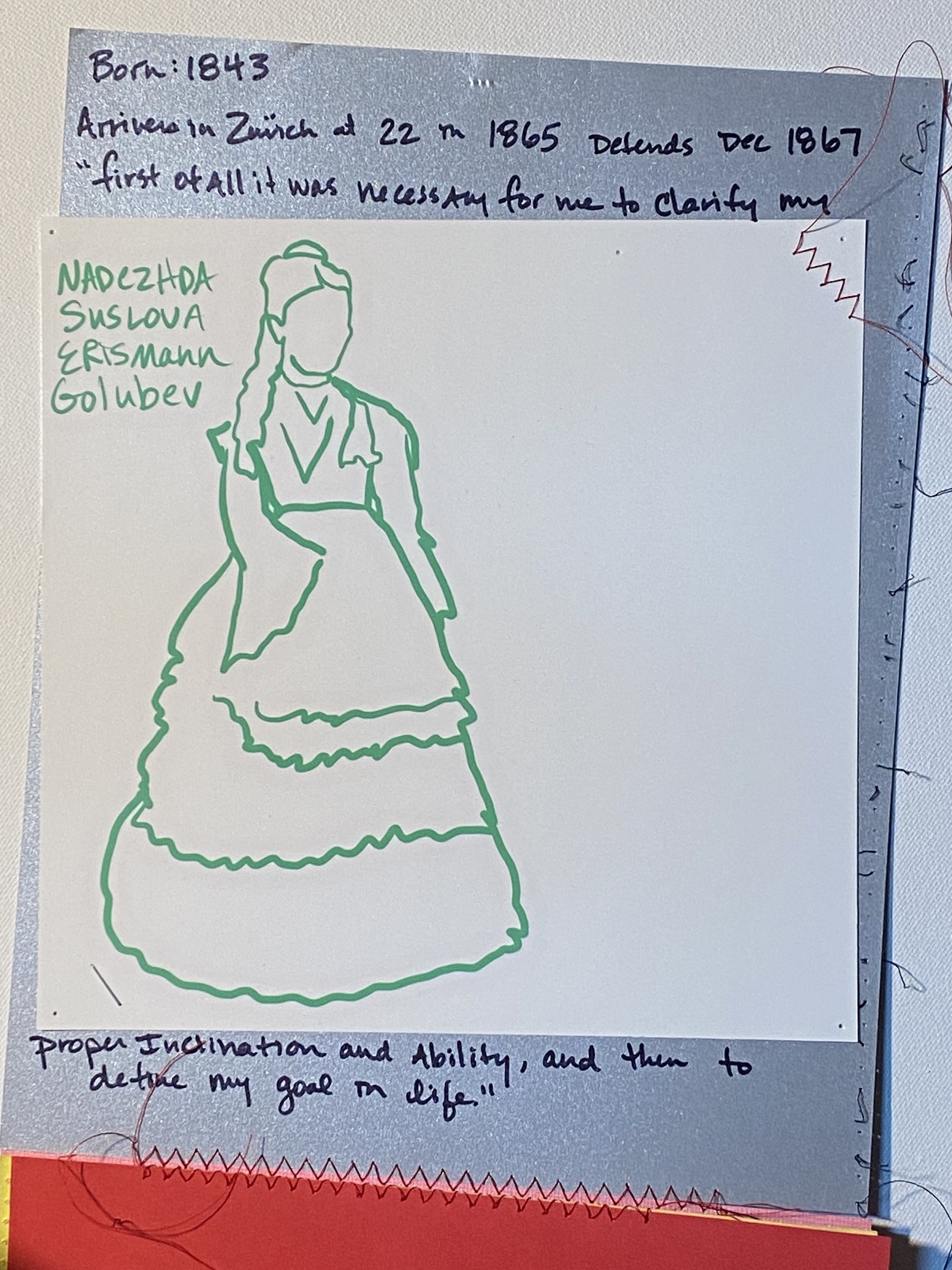

Dr. Nadezhda Suslova M.D.

#1 of 7 of The Zurich 7 (1865-1867)

Thesis: Contributions to the Physiology of the Lymph Hearts of Frogs

JUST THE FACTS*

Here are Nadia’s “Facts” from The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science

Russian physician.

Born 1843 at Panino. Father Prokofii Suslov agent for Count Sheremet’ev Two siblings. Married (1) Frederick F. Erisman; (2) A.E. Golubev.

Educated at boarding school in Tver; Petersburg Institute for Young Noblewomen; Zurich University (M.D. 1867).

Professional experience:

Petersburg Medical Surgical Academy, auditor;

private practice in St. Petersburg and Crimea.

Died 1918 at Kastel (Crimea).

Let’s explore her world

Nadia the Child

1843 - Born into a family of serfs

Prokofii Suslova, Nadezhda’s father, started out a surf. It meant meant he was legally connected to and owned by the wealthy and powerful family headed by Count Dmitrii Sheremetev. Prokofii was a highly literate and intelligent serf, he wished to marry a young women, Anna, from another village. In order to do so Count Sheremetev officially freed Prokofii (did he buy his freedom?). The rest of the serfs (hundreds of them) spent about half their working days in the grain fields of the Shermetev property and half working their own small plots, or working as artisans crafting leather, wood and brass [TFRWP, 12].

Prokofii continued to work as an agent for the count. He and his wife had a daughter Apollinaria in 1839, she was five when Nadezhda Prokofevna Suslova (#1 of The Zurich 7) was born in September. Polina, her sister, goes on to lead a very interesting life she writes stories, has an affair with Dostoevsky and becomes the subject of many of his books. To learn more, join her book club: Click Here for More

1850 - Reading at home, age 7

Prokofii was a highly skilled estate agent for the count, because of his success, they lived more comfortably and were better educated than most serfs. They were part of a growing middle class of wealthy, educated, and vocal members of society. Considered part of the ‘raznochintsy’ (non-noble) or members of the ‘intelligentsia’ (non-noble and well educated) they spent their evenings reading aloud from the journal Sovremennik (Contemporary) [recently taken over by Chernyshevsky]. Pushkin or Lermontov were favorites.

(it’s extremely likely the girls would have known Dobrolyubov when they grew up in Nizhni Novgorod, is he the one sneaking books and materials to Polina???)

FIND: Aleksandr Smirnov’s biology of Nadezhda Suslova “Pervaia russkaiazhenschina-vrach (mediz: moscow 1960 pp 1-10)

“a hen is not a bird, and a women is not a human”

“a woman has a long voice and a short mind”

1854 - 11 Years Old, Moved to Ostankino Palace

Prokofii was given increasing responsibility along with a new assignment. The family moved to Ostankino Palace, a large property of the Shermetev family near Moscow. The buildings were in need of much repair after it was raided and ransacked by Napoleon in 1812. The family was provided their own quarters in the palace while Prokofii oversaw the renovations. The count took a liking to the children, Polina, Nadezhda and their younger brother Vasilii ensuring they received high quality educations. The sisters were sent to Madame Penigka’s boarding school for noble girls, typically barred for lower classes, but a letter from Count Shermetev secured their positions [LITL4, 2].

The sisters from a serf father were wildly out of place in the very strict, old fashioned boarding school. With 80 students from ages seven to seventeen taught in the same room there was little to challenge Nadezhda. No science, but but the sisters were well taught in languages and history [TFRWP, 13].

“the mind was little developed, the heart was completely untouched, and the student was burdened with memorizations in dead disciplines.”

The Crimean War (1853–1856)

Florence Nightingale introduces the world to the benefits of women in medicine.

The Crimean War was a conflict primarily between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, Britain, France, and Sardinia. It was mainly fought over control of territories in the Ottoman Empire, particularly the strategic Black Sea and the Crimean Peninsula. The war highlighted issues of imperial ambition and religious tensions, as well as Russia's desire to expand its influence. Notable for poor military logistics and high casualties, the war is also remembered for advances in battlefield nursing, largely due to Florence Nightingale's efforts. The introduction of the telegram spread first person accounts of the atrocities of war across the globe making Florence Nightingale’s work news worldwide.

News of Florence’s work directly influenced all of the first women of medicine including Elizabeth Blackwell, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and the women of The Zurich 7.

March 30 1856 Tsar Alexander II addressed the Marshalls of Nobility saying that serfdom needs to end and asking them for the best way to accomplish this task. This speech came as the Treaty of Paris was signed ending the Crimean War. This was this the attempt to reshape the country’s defeat [KAR, 5].

The Crimean War was an embarrassment on a global scale for Russia. It showed the world how far behind they were in education, science and technology. The government rapidly assembled programs to train scientists, sending young men to Heidelberg, Gottingen, Berlin and Zurich for technical training.

One of the other major reforms was a new system of secondary schools for girls of all social classes and these classes would include sewing, drawing, history, Russian language, geometry & physics (TTEOTT, 84). Results came quickly producing a golden age of Russian scientist which would include physiologist Ivan Sechenov (learn more about him through Maria Bokova #4 of 7), chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, neurophysiologist Ivan Pavlov, embryologist Aleksander Kovalevskii and his brother paleontologist Vladimir Kovalevskii (learn more about them through Sophia The Mathematician).

The elite members of society were hopeful for a new age of serf emancipation, education reform and increased rights for women. The young people were especially optimistic.

1859 - Ostankino Palace, 16 Years Old

Tsar Alexander II visited Moscow and stayed in Ostankina. The trip went so well Count Shermetev placed Prokofii in charge of his properties in St. Petersburg which were extensive and valuable. The family would have their own living quarters and the girls would have governesses along with dancing teachers [TFRWF.

1859 - Sweet 16 in St. Petersburg

The family moved to the permanent residence of Count Sheremetev in St. Petersburg. This was a huge change for the young sisters. The city was alive with expectations for the future of Russia. The general mood at the time as presented in The Contemporary was optimistic, it was considered the “honeymoon of freedom” and led to a surge in Russian Enlightenment [TAR, 7]. Many nobles and students started schools for village children and illiterate adults, these initiatives were the foundation of Sunday schools which taught literacy and the elements of science. Science and education were the talk of society. Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species is published this year and it becomes a huge hit in Russia. [Who did the translation?] Vasilii, their younger brother attended the boys school, followed by university courses. He is befriending the young ‘nihilist’ at the university and sharing these ideas with his sisters.

Apollinaria and Nadezhda were enrolled in the Petersburg Institute for Young Noblewomen [TBDOWIS, 1252]. It’s here they meet Maria Aleksandrovna Obrucheva #4 of The Zurich 7. Maria was born in 1839 the same year as Polina, is it likely they were closer, both more political and revolutionary in their thinking. She like the sisters was a good student and excellent with languages.

Nadezhda is sixteen, Maria and Polina are both twenty-one. Nadezhda received her governess diploma but her focus was intent on her causes for women. Among them being:

emancipation, no longer property of their fathers/husbands.

equal opportunity for the acceptance into the university, especially the medical schools.

Women were not officially allowed to enroll in courses at the university, but sympathetic professors allowed women to audit courses with the permission of a father or husband [The First Russian Women Physicians, 14]. This is the year the first women were showing up in the lecture halls in St. Petersburg (TTEOTT, 84). Nadezhda and Polina had no problem getting permission from their father to attend classes. Having no rank or estates, their parents could only prosper by having children as highly educated as possible. Nadezhda’s father scornfully rejected a proposal from a “crude American type business man” wanting

They discussed their beliefs at secret meetings of secret societies trying to evade government observation (The Land and Freedom Party) Many young women were desperate for economic and personal independence and equality. Maria will go on to lead them.

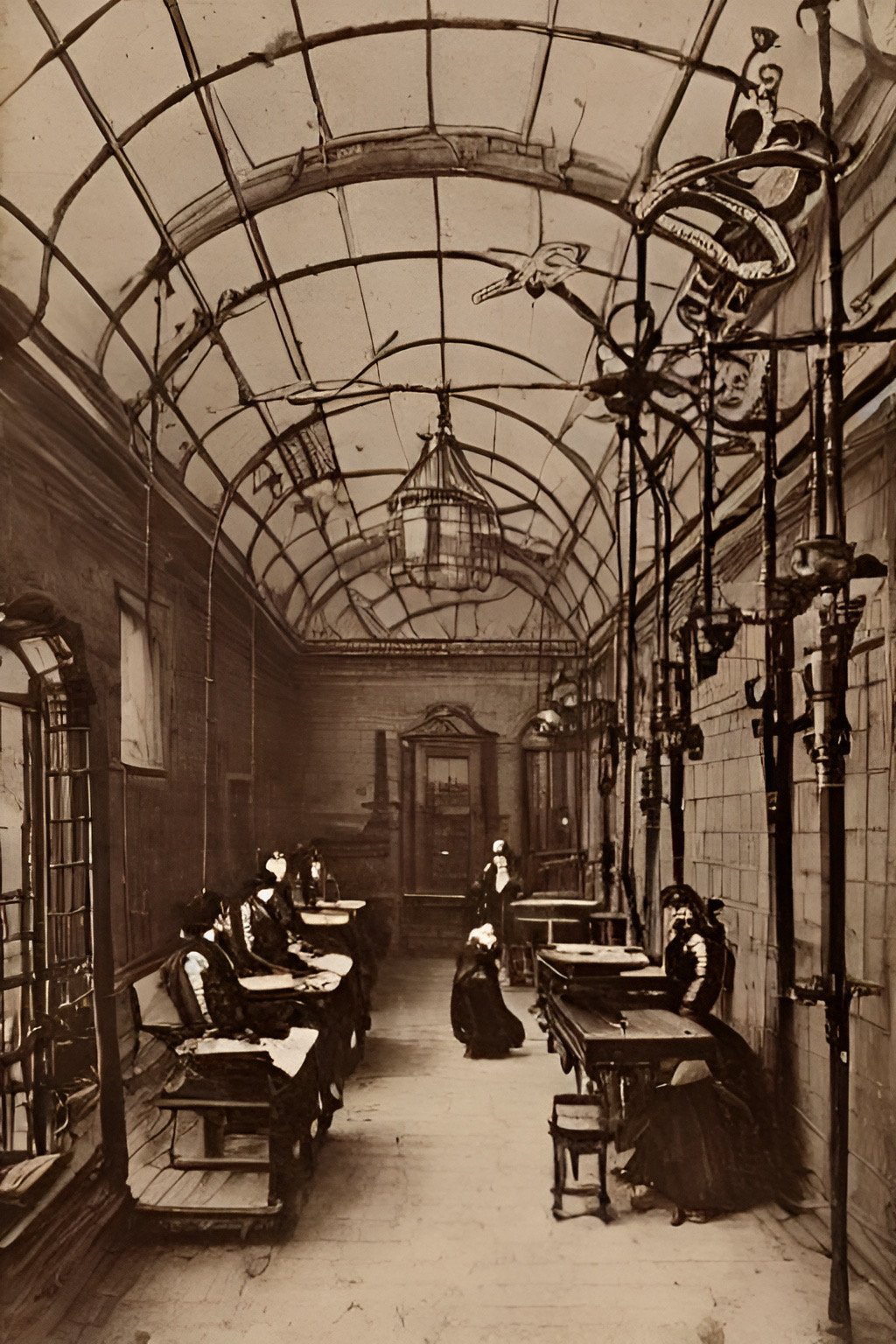

1860 - Medical and Surgical Military Academy

(Ivan Sechenov defends his medical thesis at the Medical and Surgical academy in St. Petersburg and quickly founded a physiology laboratory)

Women were a significant part of the unofficial student body at many universities, auditing classes without receiving official credit or degrees. They were tolerated by the authorities due to the liberalization of universities after the Crimean War. A few women were accepted on a semiofficial basis at the military supported St. Petersburg Medical-Surgical Academy. They could take exams and perform in the laboratory but could not receive official degrees. Two women from the Land and Freedom organization were among them, Nadezhda and Maria Obruchova (TTEOTT, 85).

Being raised as a serf Nadezhda was now an emancipated woman and could make choices as she wished but Maria could not. It took an unusual sort of arranged marriage for Maria to escape the confines of her father’s country estate so she could live and study in St. Petersburg. [Her story is here]. In St. Petersburg, the young professor Ivan Sechenov granted permission for Nadezhda and Maria to attend his lectures and set them on research projects. Summary of Sechenov's research and contributions by the women here.

The women were optimistic that soon they would be admitted as regular students with the same rights of men. A proposed draft of a new university statue included that proposal which would have made Russia the first country in Europe to grant women the same degrees and status as men.

That proposal was eliminated by the government and women continued attending courses in an unofficial status. Up to as many as 200-300 women attended lectures in search of education and employment [TFM. 6].

It was a time when the ideas of Charles Darwin were sweeping through the universities and the ranks of the intelligentsia. New scientific ideas and the expectation of revolutionary change was talked about by the young and old (TTEOTT,83). Books like Turgenev’s Fathers & Children capture the dynamic of the time, similar to the millennial vs boomer battles of the 2020s. His use of the word “nihilist” to describe the young science minded protagonist studying to become a doctor, sparked a generation of men and women to adopt the title and take on the role.

“Science was the key to modernization”

1861 - Serf Emancipation: The People vs Russia

March 3 Alexander II issued the proclamation (reform) freeing serfs. Immediately, protest erupted, many centered around the universities. Peasants were confused and unhappy with land allocations, students demanded the right to hold meetings and form lodging cooperatives and women were outraged that they were banned from universities. Protests continued throughout the year with uprisings being suppressed by force, participants were arrested and exiled to Siberia.

May A new set of university rules, mainly increasing the university fees and reducing the number of students exempt from payment (two per province). All organizations were banned, students were required to sign a copy of the new rules as a form of acceptance, this only increased unrest.

18 year old Nadezhda published two short stories in the Russian journal Sovremennik and asked for permission to audit courses at the Medico-Surgical Academy

Rasskaz v pismah (Story in Letters?)

Fantazyorka (Dreamer or the Dream).

“Sashka” is indicated by Tuve’s The First Russian Women Physicians to have been about a tragic love affair between two domestic serfs of good and gentle character whose happiness is thwarted and their lives destroyed by their callous and insensitive masters. It was said to be published in December in the Contemporary.

Another reference indicates: [In 1861, 18-year-old Nadezhda published in the Sovremennik magazine (published by N. A. Nekrasov and I. I. Panaev ) her works The Story in Letters (No. 8) and Dreamer (No. 9).]

The pamphlet Great Russian (Velikoruss) was published which suggested the people need to take action because the government didn’t intend to.

Another pamphlet To the Young Generation.

Women ask the question - Can we be official Students?

Liudmila Ozhigina petitioned the Medical Surgical Academy in St. Petersburg for the right to officially enroll as a “student” not just an “auditor” as she had been classified throughout her courses anatomy at the University of Kharkov. The president of the academy refused her petition, but the act provoked discussion in the press (TTEOTT, 85).

Varvara Alexandrovna Rudneva-Kashevarova from the Vitebsk province, she left her husband to study at the Institute for Midwives and wanted to complete her medical instruction so she could return to help the Bashkir women of Orenburg who were forbidden by their religion to visit male doctors for medical help. [KAR, 23].

Maria Mihailovna Korkunova petitioned the government to officially enroll in school.

“The Woman Question: Should women be admitted to full degree status?”

The answer to that question was favorable if it was asked in St. Petersburg, but it was negative in Moscow & Dorpat.

December Unrest about the new rules closed the universities for everyone until 1863. Five students were expelled from the city, 32 were expelled to their places of domicile and 132 were banned from the university with a severe reprimand (I suspect one of the 32 is the teacher from Sonya Kovalevskaya’s Nihilist Girl, I wonder who the students were and are these the people that seed colonies in Zurich, Berne, Paris, London, etc)

A Deeper Look at Varvara Alexandrovna Rudneva-Kashevarova

-

Varvara was boon a poverty-ridden Jewish orphan. She was raised in a family of poor teachers where she did housework. In her autobiography she mentions her childhood was filled with insecurity and loneliness, but also a conviction that she could support herself.

In her teens she ran away to St. Petersburg, falling ill from typhus she was nursed back to health, provided some money and an introduction to a retired sea captain with children her age. She was taught to read and write along with the children of the household.

-

Her adoptive father thought he had done well matching Varvara with Nikolai Stepanovich Kashevarov, a member of the Guild of Merchants, a well-to-do man with two shops.

He was twenty years older than her, but she accepted the marriage under the condition that he would provide her with an opportunity to study.

He reneged from his promise, saying "because for a merchant woman to study was not appropriate and a good wife should not be more wise than her husband."

Because of that she left and enrolled in the course for Midwives at the Princess Elena Pavlovna lying-in home.

-

At first they rejected her application because of her youth, eventually accepting her. She graduated in 1862 taking only 8 months to complete the two year course.

All she wished was: "to go even to the edge of light just to have an honest piece of bread and render some kind of service to humanity"

Varvara got her wish, she was offered a stipend to work as midwife for the irregular Bashkir troops in the Orenburg military region. Syphilis was a growing threat across the military, leaders hoped treating the women (who refused to see male doctors) could help curb the problem.

-

"I was made incumbent to serve six to eight years for the right to receive a (monthly) stipend of 28 rubles. But for that I was no longer to risk dying frum hunger and began to study with zeal."

Varvara was admitted in December of 1862 to the Kalinkinsky Hospital. Her admission was sponsored by Professor Veniamin Mikhalovich Tarnovskii, professor of veneral diseases.

(finish the rest of Varvara's Story)

1862 - The Free University & 1st Publication

Since the universities are officially closed, a group of students rounded up twenty or so professors willing hold lectures.

Professor Sechenov assigns a project to Nadezhda so she can continue her studies. She measured the influence of very light electrical stimulation on the skin to understand more about the sensory system of the body.

She Published her work: Izmenenie kozhnykh oshushchenii pod vliianiem elektricheskogo razdrazheniia [Changes in skin sensations under the influence of electrical stimulation] St. Petersburg Med Vestnik nos 21,22 [TLITL, 145].

By this time the people started to lose faith that Alexander II could completely control the unrest since the Serf Emancipation of 1861. In January, Chernyshevsky wrote an article called Letters without an Address where the author plainly is writing to the Emperor himself, stating the only choice is to abolish the censorship and appeal to the nation.

By July Chernyshevsky is imprisoned in Peter-Paul Fortress until May 1864. Nadezhda, her brother and her sister along with Maria Bokova and Pytr Bokov were all brought in by the police for inquire. The “young people” were released for a lack of evidence. Not sure about Maria’s Brother.

“But where are you young people to go who have been forbidden learning? Shall we tell you where?”

1863 University reopens in the Fall - Women Forbidden

There had been a shift, Herzen took a step back from his accusations against the Tsar. The more radical youth made up of many polish students, were not happy going backwards, they wanted to fight for more authority and freedom from Russian occupation. On January 22, a small army of 10k volunteers challenged the Russian authority, it didn’t go well and caused an even worse conditions. It’s under these harsh conditions Marie Curie was born and raised. Read more about her childhood HERE

With universities still closed, students worked on other projects:

Nadeshda publishes her work in German Veranderungen der Hautgefuhle unter dem Einflusse electrischer Reizungen [Changes in skin sensations under the influence of electrical stimulation.] Ztschr. Rationelle Med 17 155-60 [same but in german publication]

Ivan Sechenov publishes Reflexes of the Brain knowing it will likely cause a stir insinuating that the body has automatic responses in conflict with the concept of free-will supported by religion.

In the fall, universities reopen under new government charter, but women were denied access [TFM, 2]. The tsarist government connected the education of women with subversive revolutionary world views. The Tsar feared a potential assassin lurked within every “studentka” They hoped their exclusion would help settle the unrest. The St. Petersburg Medical-Surgical Academy held out longer accepting women auditors until 1864 allowing Nadezhda and Maria to continue their studies for a bit longer, but not much.

Nadezhda writes a letter to her sister Apollinaria in October saying:

“it is quite impossible to stay at the academy any longer, on account of the silly tricks played by students.”

She goes on to ask if it would be possible for her to take some lectures in Paris.

She contributes two more stories to Contemporary: “Story in Letters” (“Razskas v pismahk” Sovremennik v 103 1864 pp 141-168) was about two sisters who defended feminism and nihilism. One sister had gone to St. Petersburg to medical school in spite of the objection of parents and gossip of the neighbors and was full of enthusiasm for her prospects to lead a useful life in science. She defended her bobbed hair and nihilistic attitudes as part of her desire to be free of the past. The sister who stayed at home was misled and betrayed by a man and became a tragic figure.

“The Dreamer” was published this year as well (“Fantazerka” Sovremennik V 104 1864 pp 169-219), about the tragedy of a young gentry women in love with a poor man but coerced into marrying a more suitable partner for economic reasons. The loved one proved to be a complete cad and the heroine committed suicide.

1864 - Universities Closed for ALL Women

In February, Chernyshevsky was sentenced to fourteen years hard labor in Siberia, followed by banishment for life. Two months later Alexander II reduced the hard labor to seven years.

By May, the War Ministry which governed the Medical-Surgical Academy issued an order banning women from the institute. The lone exception being Varvara Kashevarova Rudneva [link to Wikipedia page]. Varvara was motivated to study medicine to help the Muslim women of the Bashkir ethnic group. Their conservative religion prevented them from visiting male doctors. The provincial government were in such need of female doctors they petitioned the Tsar directly to allow her to study. It is a sad irony that after finishing her studies, she was prevented from practicing medicine since all the hospitals in the region were run by the military and refused to license her.

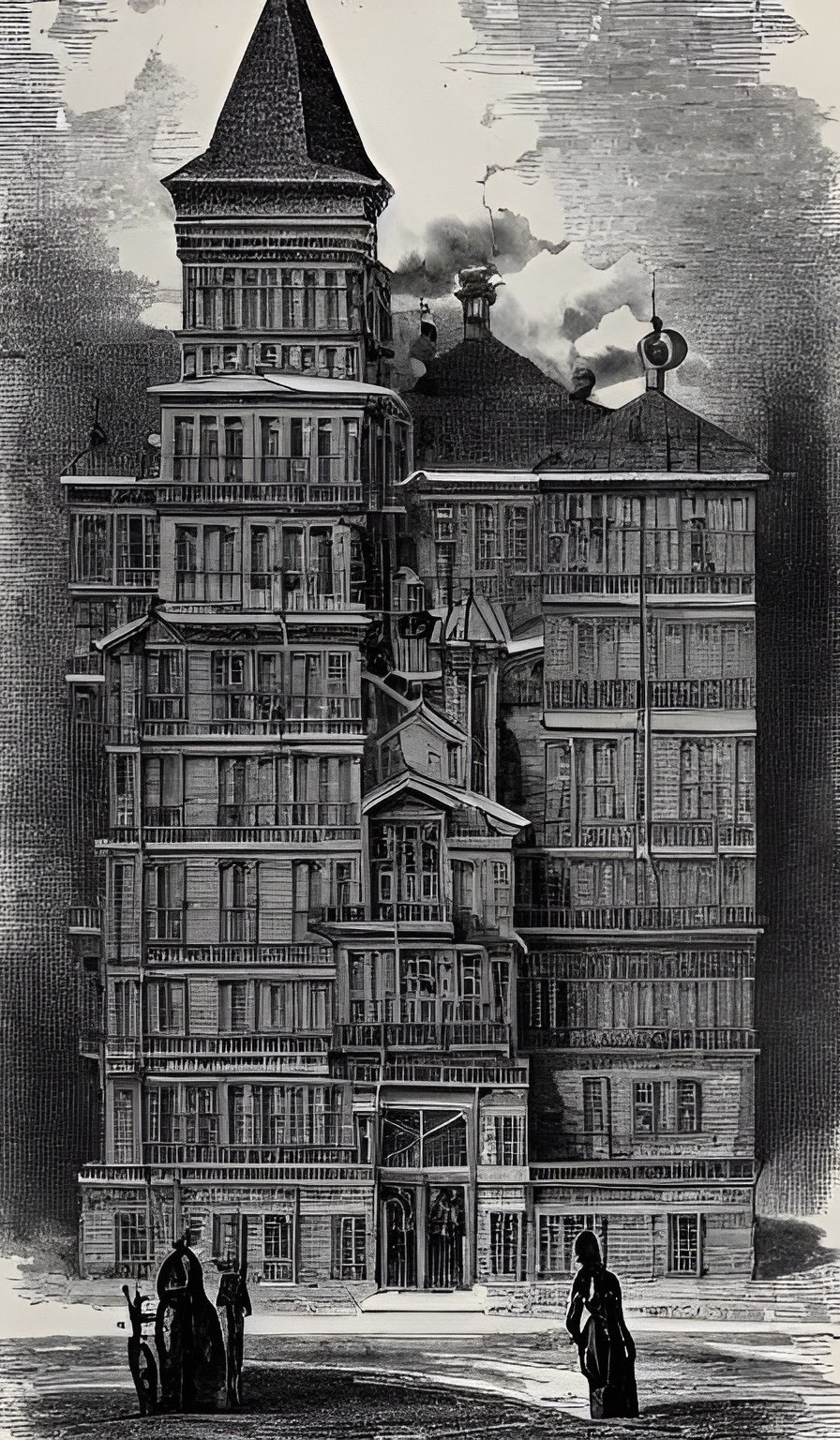

In Switzerland, Maria Kniazhnina requested permission to attend anatomy and microscopy at the University of Zurich. Zurich was a bit of an island of liberal and progressive believes leaving behind the provincial ideals (city of 35k at the time, that seems tiny now has close to a million) The medical faculty at Zurich was composed of many German professors fleeing the restrictive atmosphere of their universities, the city was considered a peaceful island in a stormy ocean according to a visiting pathologist.

In Russia, Nadezhda was under government observation, her friends were arrested. Professor Sechenov suggested she travel to Zurich to attend university courses there.

Her sister Polina publishes two stories “The Dream” and “Mikhail.” (Tuve makes it seem like Nadezhda published “The Dreamer” is that different).

At some point Sechenov recommends for Nadezhda to go to Zurich, Bokova would wait since she was engrossed in working with Sechenov on Translations of scientific works.

1865 - Escape to Zurich

[SIDE STORY - April 19th while still in Petersburg, Nadezhda receives a letter from Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. He’s sending her a letter for her older sister Apollinaria, he knows that she might be joining Nadezhda in Zurich soon. He avoids her question “does he like to feast on the sufferings and tears of others?” He references the possibility that Nadezhda will stay in Zurich for a long time and he urges her to write him and closes the letter, “I love you as one would love one’s favorite sister.”]

The University of Zurich was one of the only schools that did not require foreign students to provide proof of completing the high school finishing exam (Matura) that most European Gymnasiums (boys schools) offered. Most girls weren’t able to attend those schools, or sit for the Matura so they weren’t able to qualify to apply to most schools.

(some of Nadezhda’s naivety came from the assumption that the rest of Europe and particularly America was much more advanced in the progression of women’s education and emancipation…she was a bit surprised to show up and realize women weren’t attending the university nor did it seem like anyone wanted in)

Nadezhda arrives in Zurich, she informally audits classes by individual professors for two years, including work in pharmacology, obstetrics & surgery. She rooms in a boarding house Fluntern with Maria Kniazhnin the other woman student. Maria shows up in Polina Suslova’s diary in June of 1865 when she visits her sister and the chemistry lab of Aleksandr Andreevich Vergo. There are at least a half dozen other male russian students in the city taking classes at the university.

She was a very hard worker, classes started at 6am and continued into the evening. “she had a quite, serious temperament with deep feelings and a thoughtful, melancholy look from somewhat deep-set brown eyes.”

1866

In Her Own Words:

Nadezhda writes about the uncertain route she and her friend Maria Bokova might take, the route to medicine was unclear and blocked by monstrous obstacles.

“first of all it was necessary for me to clarify my proper inclination and ability, and then to define my goal in life…”

1867

In January, Nadezhda asked the University of Zurich for permission to take the oral examination which would qualify her medical degree. This required a decision by the University Senate and a decision by the local government of Switzerland to accept women as full time traditional students. The educational authorities of the swiss canton pushed the decision back to the faculty of the university. As the record indicates, no one opposed the move to admit Suslova as a retroactive full time student, faculty included Anton Biemer, Adolf Frick, Billroth, Edmund Rose, Hermann von Meyer, Gusserow, Carl Eberth Friedrich Horner Heinrich Frey. It’s not noted in the records but at some point the other russian woman student, Knjaznina left without graduating this year.

She officially matriculated on Februrary 1st, even though she had been a student auditor since 1865. Nadezhda becomes the first official female student at the University.

In March, Erisman is in Heidelberg, he writes a letter to Nadezhda asking her to reconsider her plan to treat the peasants in the countryside.

Summer

Suslova passes the difficult qualifying exam for the medical degree. She had planned to travel to Paris to work in the obstetrical clinics for her dissertation, but before she left she received dan invitation from Sechenov to come to Graz, Austria where he was working in the Institute for Physiology. He reached out to her because he had a tedious doctoral project for her, correlating the reflex muscle action of live frogs with the functioning of the lymphatic hearts spaced along their nerve system. (Erismann encouraged her to go to Graz).

Sechenov was studying the connection between the nervous system and the motor system using love frogs. It was a new field, expeditated by the growing use of microscopes. Sechenov noted that women often had the right kind of fine work for that type of laboratory work. Suslova did long and tedious research on tiny lymphatic hearts of frogs and obtained very good results . She established a series of analogies between the apparatus of the hearts (ganglions) and the reflex muscle mechanisms, showing the relationship of their excitability to the skin and the cerebrum. Tuve reports her thesis title is “Addition to the Physiology of the Lymphatic Hearts of Frogs”

Fall of 67

Frances Morgan and Louisa Atkins received permission to officially matriculate into the university.

Nadezhda’s defense was in December 1867 where she underwent sharp questioning In front of a large audience. Her thesis was on the physiology of the lymphatic system. [Beitrage zur Physiologie der Lymphherzen. Ztschr. Rationelle Med 31 1868 224-33] Ivan Sechenov was an unofficial advisor and worked closely with her while she completed her research, he called her dissertation “magnificent.”

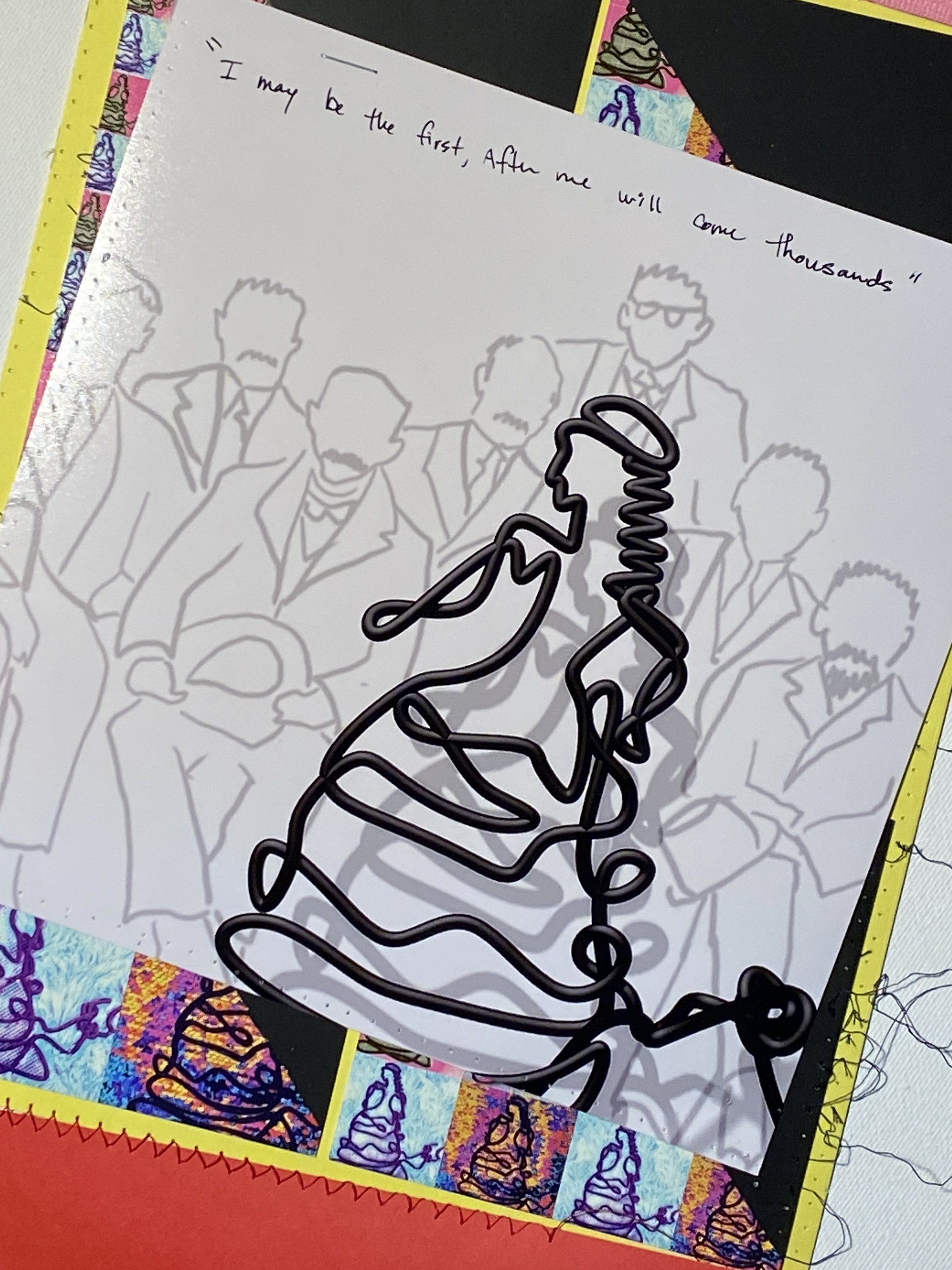

Upon completion of her defense a professor said “soon, we are coming to the end of slavery for women, and soon we will have the practical emancipation of women in every country and with it the right to work.”

“I am the first, but not the last. After me there will come thousands.”

Her degree represented the first granted to a women from a western university with high academic standards. It was widely reported across Europe and America and literally opened the door to a new era of education for women.

NEWS OF DR NADEZHDA SUSLOVA M.D.

The event caused a big response with many magazines publishing reports about her degree. Famous people including Alexander Herzen greeted Suslova when she returned to Russia in 1867.

1868

After getting to know Suslova, Erisman became so interested in the problems of Russia he wanted to marry her and immigrate to her homeland. They both considered their areas of work more important than their personal desires. Suslova wished to go to Orenburg province to render aide to the Moslem population of the Kirghiz steppes. Erisman wanted to relieve suffering too, but wrote to Suslova from Heidelburg in March of 1867 asking her to consider remaining in the cities where something could be accomplished. Who would listen to her in the country?

Tuve (The First Russian Women Physicians) indicates the couple were married in February 1868, Maria Bokova who had separated from Pytr attended with Sechenov, Maria was in Graz not sure of Sechenov was there too, she was heading to Zurich for enrollment. After the wedding Erisman heads to Heidelburg to study opthamology while Suslova returned to St. Petersburg.

Another Version:

April 16th 1868 Nadezhda Marries Friedrich Huldreich Erisman (they met in late 1865 or 1866). After the wedding, Nadezhda returns to St. Petersburg to attempt to formalize her medical license in Russia while Erisman studies in Heidelberg and Berlin [TBDOWIS, 1253]. Wonder if Erisman crosses paths with Sofya Kovelaveksya and others in Heidelberg??? Also is his involvement with the International keeping him from going to Russia right now???

It was not easy when Suslova returned to Russia. After much campaigning she was required to take a special exam administered by professors of the Medical Surgical Academy. Upon passing she was granted status as russia’s first woman doctor, but without the bureaucratic title and social status given to male doctors. It was a step in the right direction. Many women of the middle and upper classes welcomed the opportunity to discuss medical problems with a doctor of the same sex.

Nadezhda continued her work in Russia and was one of the first to note that blindness in infants could be caused by exposure to gonorrhea during passage through the birth canal. Not sure when Fredrick Erisman arrives in Russia, he will eventually hold the highest position in public health in the Russian Empire.

1869

Erisman arrives in St. Petersburg with a Russified name, Fedor Fedorovich. He passed the required medical examinations and joined Suslova in private practice. It wasn’t enough for Erisman. He wanted to serve humanity in a broad way.

More on F. Erismann from the footnotes of Knowledge and Revolution pg. 178, reference 59.

“…F. Erismann was one of the very few Swiss students who at an early date favored the study by women. He had married Suslova and gone to Russia with her; in St. Petersburg he practiced ophthalmology. The couple returned to Zurich for a time in 1872. Erismann, appalled by hygenic conditions in Russia, decided to devote himself to this field and became an auditor again. He became a member of the Greulich section of the International in Zurich; his signature figures under several documents emanating from it. He also continued to take a lively interest in the affairs of the Russian colony. After his divorce from Suslova he remarried the Russian student Gasse. For is relations with the International he at first was not admitted into Russia.

1870

Suslova-Erismann publication [On the upbringing of children in their early years]. In this publication Suslova reassured mothers that problems such as crossed eyes were not caused by anything mothers had done during pregnancy or the days after birth. Suslova was the first to indicate the red inflamed eyes of young babies was not caused by dust or bright light, but by infection of gonorrhea acquired while passing through the birth canal.

1872

In the footnotes of Knowledge and Revolution it says the couple returns to Zurich for a time this year. He was appalled by the hygienic conditions in russia and devoted himself to this sector

1874

The couple divorces. Erisman was a marxist, is this what drove them apart?

1885

Nadezhda marries A.E. Golubev, a professor of histology. They move to Kastel where she practices medicine. During her time there she builds an elementary school and a library and contributed large sums of money to worthy causes [TBDOWIS, 1253].

Selected Resources:

[LITL4] Creese, M. R. S. (2015). Ladies in the Laboratory IV: Imperial Russia's women in science, 1800-1900: A survey of their contributions to research. Scarecrow Press.