Maria Obrucheva

Maria Bokova

Marie Bokowa

Maria Sechenova

Mariia Alksandrovna Sechenova-Bokova

Zurich 1868-1871

Thesis: On the Doctrine of Keratitis

She is described in The Biological Dictionary of Women in Science as:

Russian ophthalmologist. Born 1839. Daughter of General Aleksandr Obruchev. One brother. Married Petr Ivanovich Bokov, Ivan M. Sechenov. Educated Petersburg Institute for Young Noblewomen; Petersburg Medical Surgical Academy, auditor; University of Zurich (M.D. 1871). Professional experience: worked in clinic in Kiev. Died in 1929.

1839

Born the daughter of an army general, Alexander Afnasevich Obruchev from Tver Oblast. He was a landowner with a traditional, conservative outlook on society. Noble parents were worried about the attitudes of the new generation, they preferred the conventional roles of wife, hostess and mother. Privilege and rank were acquired through husbands and fathers [TFRWP, 14]. The primary goal for his daughter was to wed her to another general or wealthy landowner suitable for marriage (meaning had significant wealth). Woman had no rights of their own, they were legally considered property of their fathers until they became property of their husbands. This was consistent with society across many countries, at least in Russia women could inherit land. It was one of the few advantages they held over women in other countries.

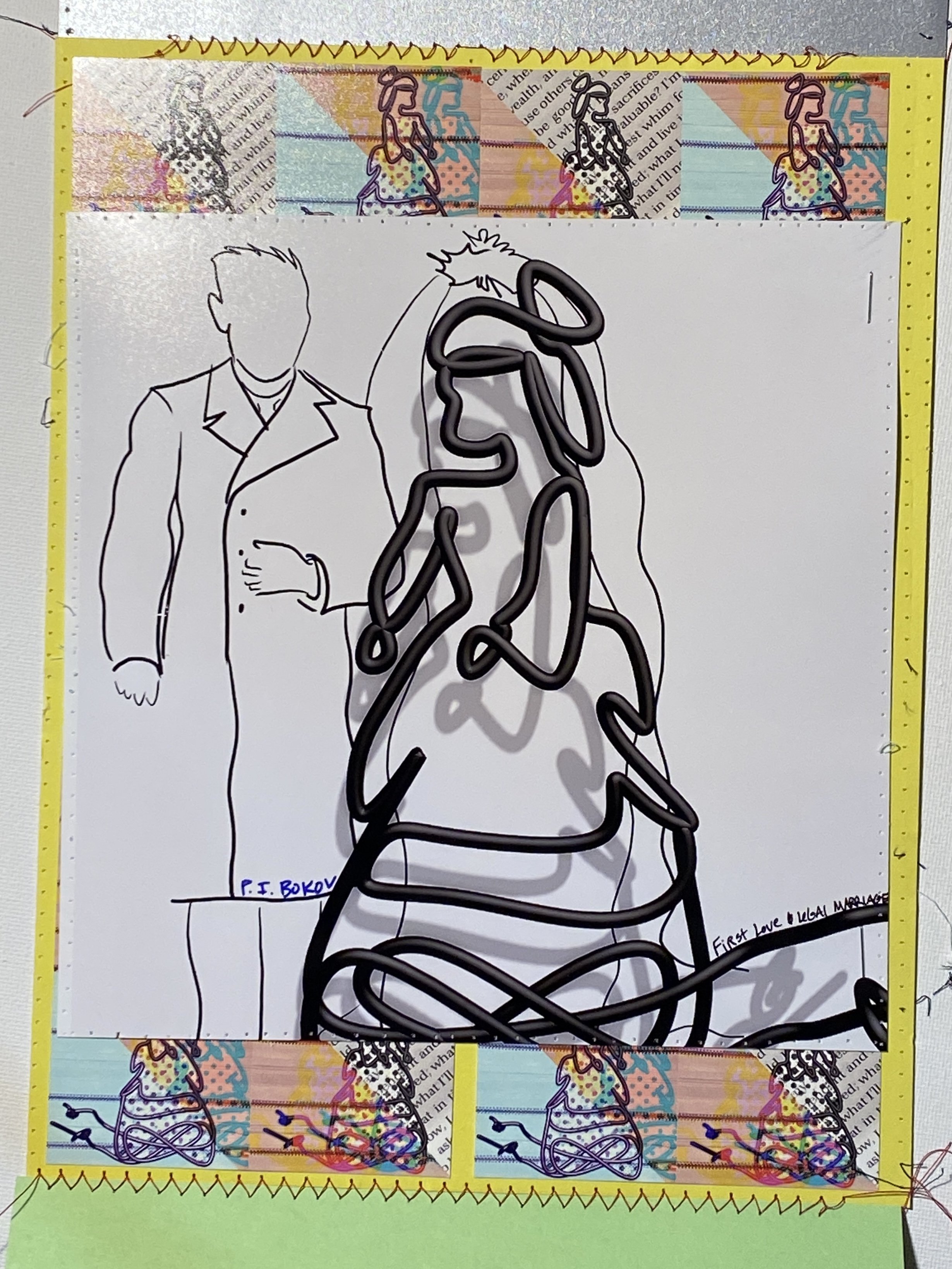

Some women found it intolerable to live under such strict environments, trapped at home. They sought to escape through mutually beneficial “marriages.”

“In no other country in Europe do they hurry into marriage as we do in Russia, and no where do women suffer as much for it as ours. Every day we see brides of sixteen, among them weakly developed girls, underdeveloped or just beginning to develop, and no prevention of pregnancy. Too often we see women of twenty with three children and pregnant with a fourth. These women, emaciated, exhausted, often accost doctors with entreaties to teach them not to have more posterity, and some implore to have abortions.” (Tuve)

1852

Chapter 1 of What is to be done? Starts this year, if this timeline is correct Maria would be 13. The chapter suggests she started attending private school at 12 and had piano lessons from a kind but drunken piano teacher.

1853

Still from Chapter 1 of What is to be done? Indicates by this age (fourteen) she does all the sewing for the entire family.

1855

As she turned 16, she was shouted at by her mother “scrub that face of yours - you’re as dark as a gypsy girl! You’ll never get it clean, I don’t know who you take after.” By this age she had stopped taking school and had started teaching lessons at that very same school. Her mother found additional pupils for her.

1856

According to the timeline from What is to be done? Chapter 1 “The Fool” takes place the morning of July 11, 1856. ‘Vera’ is already living in Petersburg when she hears the news of her husbands death. If this timeline is correct that makes Maria 17 and a widow, but she wouldn’t have known Sechenov yet would she??? He doesn’t start lessons in St. Petersburg until 1860.

She get’s a letter July 20, 1856 from Berlin, she responds from Petersburg August 25, 1856.

1859

By 1859 we know she is enrolled at the Petersburg Institute for Young Noblewomen [TBDOWIS, 1252]. It’s here she meets Nadezhda Suslova (#1 of the Zurich 7) and her older sister of the same age, Polina.

They are all members of the Land and Freedom movement, inspired by her older brother. He is in the military, but is pushing for reforms.

Pytr

Bokov

The First “Husband”

Keep scrolling for more of Maria’s Life

Pytr .I. Bokov, born a serf who managed to become a student at the University [IS, 57]. He was hired to tutor Maria’s older brother. A friend of Botkin, Bokov had graduated from the Medical-Surgical academy and established a general medical practice in Petersburg. He was described as a man of infinite tact and kindness with unusually handsome features. He talked to patients with such a soft manner it seemed as if he suffered from their maladies as well.

Unlike other men, Bokov engaged Maria in intellectual discussions rather than commenting on her beauty. Although an initial plan for Maria to secure a governess position failed, it pushed her to consider drastic options like suicide to escape her confining circumstances. Recognizing Maria's desperation and his own burgeoning feelings for her, Bokov proposed a solution: he would complete his academy work in three months, become a doctor, and they could marry. Maria insisted on maintaining her own financial independence to avoid any power imbalance in their relationship. Both agreed to respect each other's autonomy within the union. Maria needed Pytr’s permission as her husband to leave home and travel to St. Petersburg to attend the courses of higher learning. As many as 60 other women are attending courses. Petr Bokov suggests Nadezhda and Maria enroll with Sechenov when he opens his lectures to the public..

Nikolai CHernyshevsky was one of Bokov’s patients [IS, 57]. He was a political intellectual passionate about the struggle of peasants, the old regime and solidified the ideas backed by the ‘land and freedom’ party.

Bokov encouraged Maria to study English so she could translate Darwin’s work into Russian [TBDOWIS, 154].

The relationship between Maria, Petr Bokov and Ivan Sechenov will become a major plot of the book What is to be Done? it will be written in 1863, click one of the buttons below to explore the world of literature and publishing houses at this time featuring Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Nadezhda Suslova.

The political discussion of the time produced a massive wave of art, literature, science. The new wave of middle class young people flee traditional paths and seek education through reading, discussions and university lectures. A new wave of popular young scientists emerge as Darwin’s ideas sweep the continent. The debates are over action vs reaction, are we made up of something more than us or are we biological machines. To encourage the education of the public, lectures are established at the universities. Women who are able flock to the courses alongside men. One women, who had been trapped at home Maria Obruchova is now married and attending classes in St. Petersburg as Maria Bokova alongside he husband Petr Bokov.

Ivan Sechenov’s

Timeline Before Maria

Moscow

1851 Applies to the entrance examinations for Moscow University, passes exam, starts September 19th, studies anatomy, physics, chemistry, botany, zoology, mineralogy and theology (obligatory).

1852 2nd year, studies organic chemistry, pharmacognosy, general pathology and therapy, physiology and comparative anatomy.

1853 3rd year, studies the main medical subjects but Sechenov finds the material not theoretically substantiated, chooses physiology as his post graduate work.

1854 4th year, treats patients at the clinics of Moscow University, Sechenov’s mother dies, he requests from the estate 6000 rubles and freedom for his serf F.V. Devyatnin.

1855 continues work in the clinics, publishes first paper, studies physiology and comparative anatomy independently.

1856 Sechenov applies to be admitted for the examinations for the Doctor of Medicine, passes exam, graduates from Moscow University cum laude

Berlin

1856 Sechenov begins at Berlin University, studies comparative anatomy (Muller), analytical chemistry (Rose), Electrophysiology and general neurophysiology (Du Bois-Reymond), Qualitative and quantitative chemical analysis. Uses a galvanometer with frog’s muscles and nerves and studies the composition of “animal liquids”

1857 Begins work on his thesis Physiology of Alcholic Intoxication

Leipzig

1857 Begins work in Funke’s lab, studying metabolism.

Vienna

1858 In the Spring, starts work in Karl Ludwig’s lab on the influence of alcohol on oxygen consumption by the blood. Invents a new type of absorptiometer. (Botkin? arrives in Vienna)

Heidelberg

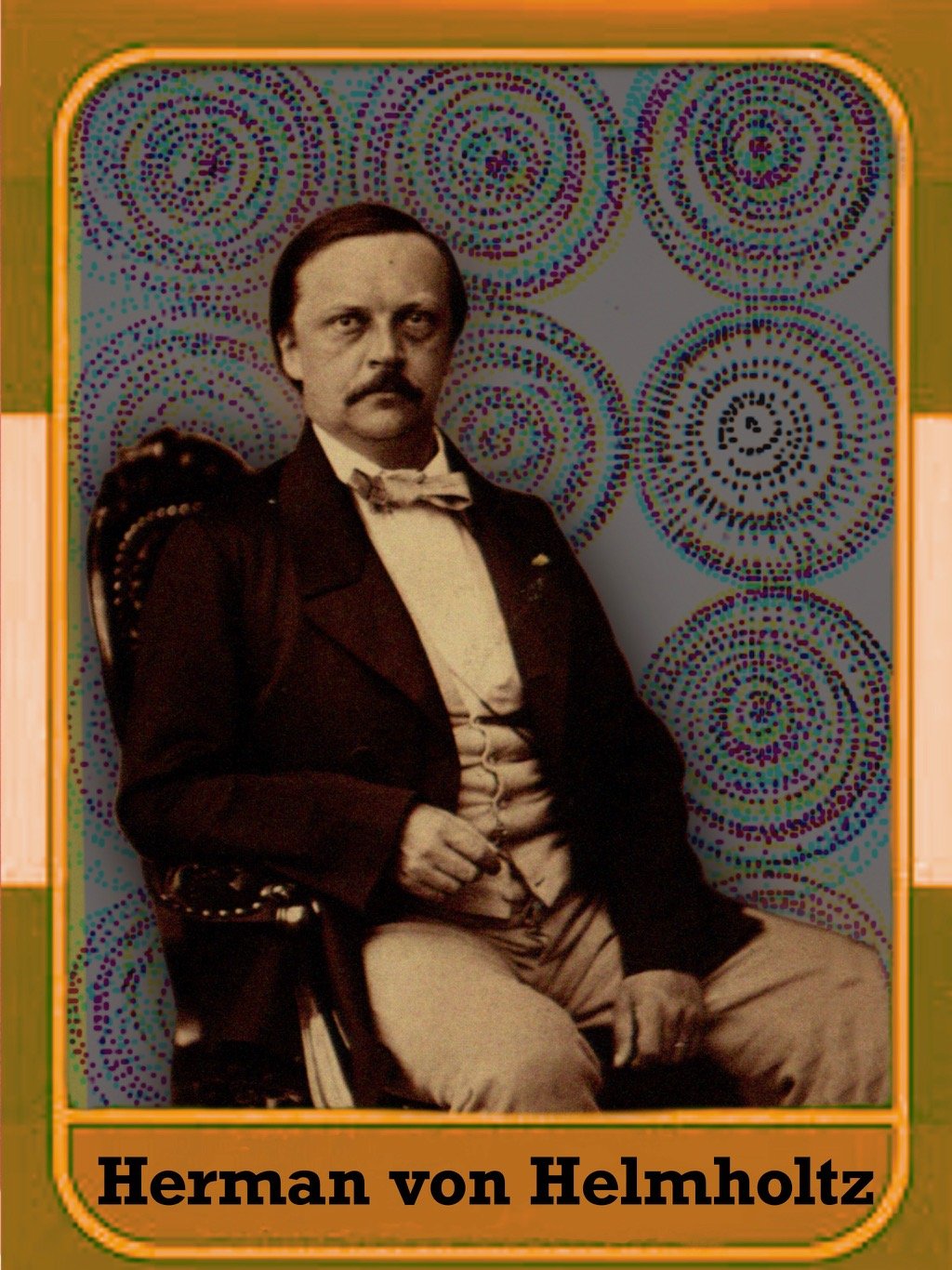

1859 Begins work in Bunsen’s lab studying gas analysis of air and carbon dioxide. Works in Helmholtz lab on the fluorescence of the eye media. Receives an invitation to work at the Medical-Surgical Academy in Petersburg.

Petersburg

1860 Arrives to start work, defends his thesis for an MD degree, organizes a physiological lab and lectures on a regular basis, prepares his book About Animal Electricity

Ivan

Sechenov

The Second Husband

Keep scrolling for more of Maria’s Life

A student of the physicochemical school of physiology, the aim was to “reveal the truth that there are no other forces operating within the organism except physical and chemical ones [IS, 33].” There is no “vital” or life force separate from the ones we can observe.

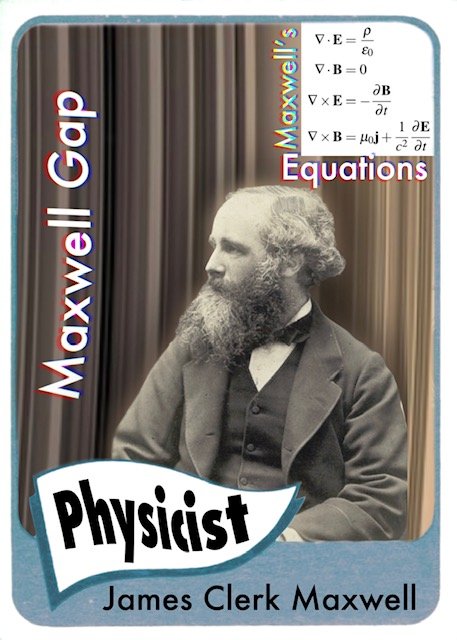

In Berlin, Sechenov studied electrical phenomena in the nerves and muscles with Du Bois-Reymond.

In Bonn, Sechenov repeated the experiments on spinal reflexes first described by biologist Edward Phluger. At the time, the reflex motion was thought to be completely different from any other, independent from consciousness. Reflexes were thought to be handled by the spinal cord not the brain because the brain is the container of consciousness and volition making mans actions reasonable. What they found was that a decapitated frog when placed on a table would craw, but in water would swim. How does a brainless frog know the difference between a solid and a liquid? There was something more complex at work.

“Helmholtz was the first man ever to see the interior of the living eye, its retina, which is sensitive to light.”

-

Helmholtz’s "On the Conservation of Force" solidified the concept that energy cannot be created or destroyed only transformed from one form to another. He wanted to apply that scientific understanding to organisms. Previously the only tool of the researcher was a scalpel, but new instruments were invented that changed long held beliefs. Helmholtz invented the ophthalmoscope, which allowed him to look deep into the eye like no one before.

Newton believed the speed of an organism’s signal along a nerve was close to the speed of light. Helmholtz invented a technique to accurately measure that speed and it turned out to be 120 meters per second (~268 MPH) which is very fast, but not close to the speed of light which is 299,792,458 meters per second (or about 670,616,629 Miles per Hour). MANY people cold not believe the result, the editor refused to publish it, but the results were easy to replicate and soon everyone knew the truth [IS, 34].

Heidelberg

In Heidelberg, Sechenov worked with both Bunsen and Helmholtz. Helmholtz assigned him to study the response of the transparent media of the eye to ultraviolet rays. Sechenov observed the fluorescence of the retina under these invisible rays.

Sechenov crossed paths with Helmholtz when discussing the mechanics of the eye, being both involuntary and voluntary.

Because of a relative’s death due to alcoholism, Sechenov was interested in how alcohol affected various tissues, organs and the organism as a whole. He studied the effects of alcohol on the respiration, temperature, nitrogen metabolism, nervous system and various organs. These research subjects would go on to form his doctorial thesis [IS, 37].

In Vienna his work with Ludwig (who invented the first methods of recording continuous blood pressure) they studied the effects of alcohol on circulation. They revolutionized the science of blood gasses. Because of the friendship between the two, over 50 Russians (including the women and Pavlov) would get a chance to work in his lab.

Ivan Sechenov’s

Timeline with Maria

St. Petersburg

1861 Gives public lectures on What is Called Vegatative Acts in Animal Life, assists on an operation on Medeleev’s right eye, MEETS MARIA BOKOVA AND NADEZHADA SUSLOVA

1862 January - the universities are closed, then opened, then closed assigns research topics for Bokova and Suslova, BOKOVA PUBLISHES IN MEDITSINSKY VESTNIK HER PAPER A METHOD TO PRODUCE ARTIFICIAL COLOR BLINDNESS.

Paris

1862 By September is working in Bernard’s lab experimenting on frog’s brains, testing the reflexology of the spinal cord. Finishes paper on central inhibition and publishes in three languages (I wonder who prepared the translations).

1863 Starts the year finishing work with Regnault on thermometry to study “animal heat” tours his central inhibition phenomenon to Ludwig, Brucke in Vienna and Du Bois-Reymond in Berlin.

St. Petersburg by May is working for Sovremennik, receives Demidov Prize for is book About Animal Electricity. Censors prohibit the publication of his paper unless they change the title to Reflexes of the Brain. By November he is giving lectures of his theories to students at the Medical-Surgical Academy. December, Sechenov is decided to be the mastermind of the progressive intelligentsia, propounder of nihilism and amoralism

1864 Sechenov is promoted to ordinary professor. May, Bokova’s application to become an official student is rejected, indicating women are barred from attending classes (he starts looking abroad for options).

1865 Starts the year with more lectures for students at the Medical-Surgical Academy. Meets IlYa Mechnikov and Aleksandr Kovalevsky (Here is our connection to Sophia Kovalevskaya she will marry Alexsander’s younger brother Vladimir)

1866 More public lectures

APRIL 7th 1866 The copies of Reflexes of the Brain were taken by the Censorship Department, Sechenov and associates were arrested.

October 1867 Supervises Nadezhda Suslova in preparation for her docterate thesis which she defends in December (is he there? is Maria there?)

1868

[finish this timeline from Ivan Sechenov book - he’ll run into Sofya Kovalevskaya in the fall? when Lectures begin - PI Bokov lends them a skeleton to study physiology]

St. Petersburg

1861

The St. Petersburg Medical-Surgical Academy was the first to admit women as medical students on an informal basis only. They could work in the laboratories and were encouraged by the progressive professors (not to mention free lab work)

[LINK TO PDF Koshtoyants used archival sources extensively and was the first to publish Sechenov’s letters from Graz to Maria Bokova. Another volume by Koshtoyants, Ocherki, provides some useful information on the history of experimental physiology in Russia. Can’t find version of Koshtoyants paper

THE OBRUCHEV AFFAIR

October 1861 Maria’s brother, Vladimir Alexandrovich Obruchev, after retiring from military duty, started working at Sovremennik. He was close with Chernyshevshy. He was arrested, for distribution of the “velikoross proclamations”

July - Pytr Bokov was in Chernyshevsky’s apartment when the gendarmes burst in to seize him and take him to Peter and Paul Fortress, but charges against him are eventually dropped. Pytr, Maria Bokova, Nadezhda Suslova her brother and her sister Polina were all brought in for inquiry.

November 3 1861 Maria’s brother is moved to Peter and Paul Fortress

December 2 1861 Maria’s brother is put to trial, even Emperor Alexander II is following along. The universities are closed and will remain closed until 1863.

1862

February Maria’s brother is convicted and sentenced to hard labor and therefor civil execution. He was taken to a scaffold, tied to the post and a sword was broken above his head indicating a total deprivation of all civil rights, he was put in irons and taken away [IS, 62].

March Professor Platon Pavlov was exiled from the University and country, with no trial.

Sechenov and Mendeleev worked to organize public lectures counting on expelled students to audit them.

By July Chernyshevsky has been inprisoned (likely along with Maria’s brother) in Peter-Paul Fortress.

Summer - Maria is taking Sechenov’s supplementary physiology course (is this work she is doing with Nadezhda towards her papers?) Authorities had banned women from lectures at the university. To help them in their studies Sechenov assigned research topics to two of his women students.

In the Fall, Sechenov goes to Paris for the university year 62-63(????) [IS, 70]. [Is Maria with him? Has she been arrested?

-

Bokova was to verify Helmholtz's theory of color vision. His theory was that there are three different nerve elements to perceive the colors red, green and blue. All other colors and their shades are produced by these three. Maria gave her subjects glasses with red lenses. The subjects described the loss of sensitivity to the color red.

Another description of her work: Bokova’s project was to compare the results obtained from wearing dark glasses (so loved by the nihilists) with the known symptoms of congenital color blindness.

-

Suslova worked on a different sensation. She worked to verify the data on the threshold of the tactile sense, ie the smallest stimulus that gives rise to the slightest sensation of touch.

-

The results of both research topics were published in 1862 by the Medical Herald. They were the first experimental research papers performed and completed by women.

-

Histories written by men, feature men. One review of Chernyshevsky's work seems to indicate there were no women involved:

"It was for this young generation that the book had been written. The answers to the question What is to be done? lay in student 'communes' (groups of young men living together and sharing all their possessions), and in cooperatives of production through which these young men could reach the town population. These 'communes' did, in fact, become nests for all the Populist conspiracies of the 'sixties. In the last chapter Chernyshevsky pointed out in veiled terms, obscure to those who knew nothing of him, but clear enough to those who understood his aims the revolutionary outcome of these ventures of self-education and social activity. The hero of the novel was a, typical revolutionary of the times. A man for whom life's problems are not solved by an affirmation of personal freedom, but by virtue of the task which awaits him and his dangerous and uncompromising opposition to despotism.

Most women think the hero of the story is Vera and her group of women who form a sewing collective and illustrate how to work together in a new way.

1863

Nikolai Chernyshevskii’s What Is To Be Done? is written and published within four months, between December 14, 1862, and April 4, 1863 while he was imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg. The first part of the manuscript was submitted to the prison censor, who, whether carelessly or for devious purposes, passed it and forwarded the manuscript to the censor of the journal Sovremennik. What Is to Be Done? appeared in numbers 3, 4, and 5 of Sovremennik for 1863, and was published subsequently as a separate volume. The plot is based on the real life events of Maria Obruchova, her 1860 marriage to Peter Bokov and their relationship with Ivan Sechenov at the university. Due to the popularity of the novel Maria became a hero and a role model to young women of the new generation. Influencing Sofya Kovalevskaya and many others.

A rough draft, lacking sections 19-23 of Chapter 5 and all of Chapter 6, was discovered much later in the archive of the Peter-Paul Fortress and published in 1929.

The influence of the book can’t be understanded in society.

It’s this year Maria begins translating with Sechenov. She translates Darwin and physiology textbooks, she was noted for her skills with language, her knowledge of science her diligence and neatness.

“We worshipped the novel while reading it with a piety that did not allow a smile to pass one’s lips, as if we were reading a prayer-book. The influence of the novel on our society was enormous”

1864

Professor Sechenov’s was deeply affected with the government’s decision of 1864 to cancel admission of women to the Medico-Surgical Academy. Maria Bokova along with Nadezhda Suslova, who had been studying at his laboratory since 1861, were now prevented from entering the Academy as a student. Sechenov’s petition to the Conference of the Academy was of no avail. He was ready to leave the Academy and go with Maria to Vienna to work at Ludwig’s laboratory where she could study obstetrics at one of Vienna’s clinics. It seems that Pavlov was right suggesting that the Reflexes bears evidence of “a strong emotional upheaval”: it was “a stroke of genius in Sechenov’s thought,” with a kind of “personal passion.

Eventually Maria was arrested along with Petr. Also Arrested was Chernyavsky, he was convicted of subversion, largely on the basis of false evidence, and sentenced to fourteen years at hard labor (later reduced to seven), to be followed by permanent exile.

1865

?. Nadezhda leaves for Switzerland

Maria remains to continue working with Sechenov, translating scientific works.

Where is Maria?

1866

1867

Nadezhda graduates at the end of the year, is she here to watch?

1868

Februrary - Nadezhda & Erisman marry in Vienna. Maria is in attendance with Sechenov. They are coming from Graz, Maria is on her way to Zurich where she will start medical school.

Fall

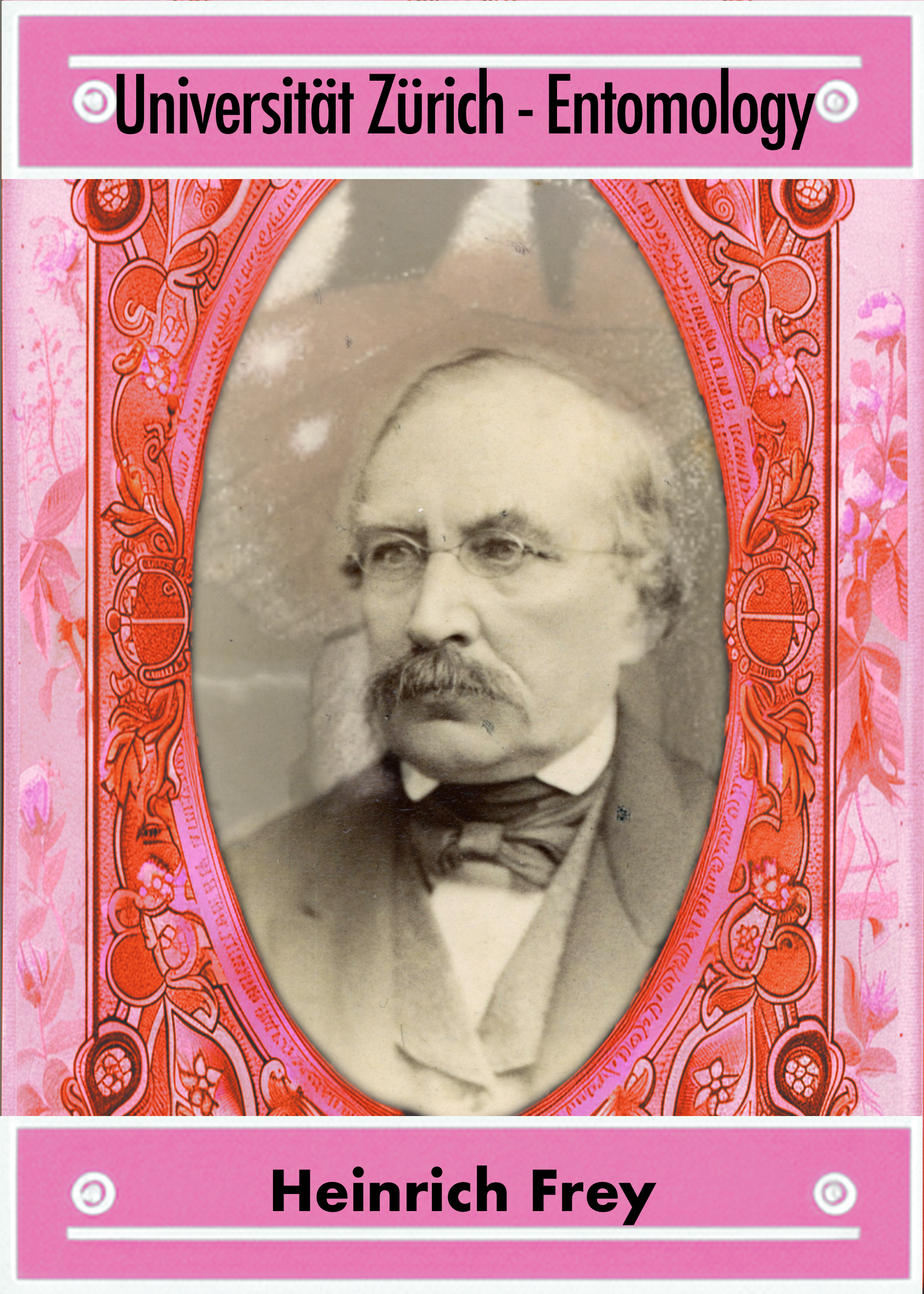

She was the oldest of all the women, 29, when she started at the University of Zurich along with Susan Dimock and Marie Vogtlin

Maria was interested in ophthalmology, she studied the previous 10 years’ worth of work by Friedrich Horner on hypopyon-keratitis.

Ivan Sechenov’s

Timeline with Maria

1866 More public lectures

APRIL 7th 1866 The copies of Reflexes of the Brain were taken by the Censorship Department, Sechenov and associates were arrested.

October 1867 Supervises Nadezhda Suslova in preparation for her docterate thesis which she defends in December (is he there? is Maria there?)

1868

[finish this timeline from Ivan Sechenov book - he’ll run into Sofya Kovalevskaya in the fall? when Lectures begin - PI Bokov lends them a skeleton to study physiology]

“News of Suslova obtaining her doctor’s degree in Zurich indicated to me what direction to turn. Not the thought of my duty to the people, not the conscience of the “repentant nobleman” impelled me to study in preparation for a position as village physician. All such ideas were of later growth, under the influence of literature. My main moving influence was a mood. ”

1870

“An excess of vital force” fed a growing colony. Over the summer, 6 Russians matriculated at the university, 3 were women.

No numbers for 1871 - Maybe due to Franco-Prussian War

by 1872 the numbers were 75 and 45

by 1873 it was 153 Russian students 105 were women.

The total number of the Russian colony grows to over 300

1871

Before graduating, she volunteered to go to the Franco-Prussian battlefield near Belfort. The expedition was organized by Professor Rose, the group included August Forel. She was the only women on the expedition she “won all hearts by her steady and self-sacrificing efforts in behalf of the wounded.”

In June prior to graduation there had been concerns about the growing number of Russian students at the university. Professor Frey praised her ability and the other women’s ability in working with the microscope. Professor Rose praised her experience on the battlefield. Professor Meyer, the physiologist who held a personally negative attitude towards women’s education made quite note that it never made a difference having men and women together in the classroom.

She received her degree in just three years, her dissertation titled “On the doctrine of keratitis”

December 10th Maria she received her license which allowed her to practice medicine in Russia [IS, 234]. She didn’t stay for long. She traveled to Vienna to work on ophthalmology, Nadezhda was there and we know Sechenov was there too but it’s difficult to find any information for this period of time.

1872

She worked in Vienna Dr Walker Dunbar was there too along with Dr Susan Dimock. She returned to Russia and worked as a researcher at the Russian Academies of Sciences and Medicine on color blindness and color vision. For a while she was working in Kiev and Sechenov was in Odessa.

1876

Sechenov get’s an appointment in St. Petersburgh, Maria returns with him.

1880s

“I’m very pleased with the quantity of wheat my experimental farm produced this season. I have many plans and improvements to make for next season.”

1888

She officially married Ivan Sechenov

It’s stated that although she had a successful but short career as a doctor, she should be most well known for her scientific translations. Specifically the translation of works on physiology (likely that of sechenov) and of Charles Darwin. Her mastery of foreign languages was so great and her standards were so high her work required no editing [TBDOWIC, 155].

Other References:

[IS] I︠A︡roshevskiĭ MG. Ivan Sechenov. Moscow: Mir Publishers; 1986.